|

作者:Tim Ryan 创造设计文件的目的是传达游戏创意,描述游戏内容,呈现执行计划。设计文件是制片人宣传目标,设计师倡导理念的权威材料,也是美术人员和程序员的任务指南。不幸的是, 有时候设计文件很容易被忽视,或者达不到制作人,设计师,美术人员以及程序员的预期。本文将通过展现撰写设计文件各部分内容的相关指导原则,助你根据项目和团队需求制 作文件。 在本系列文章的第一部分中,我将描述创造设计文件的目的,以及遵循这些原则的好处。本文包括编写设计文件的前两个步骤,即编写理念文件和游戏提案。而在第二部分,我将 进一步阐述撰写功能说明,技术规范以及关卡设计的相关原则。  game design document(from willdonohoe.wordpress.com)

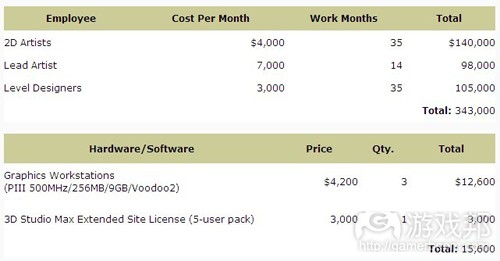

撰写设计文件的目的 从广义上来说,撰写设计文件的目的便是详细阐述游戏观点从而让开发者更好地执行它。它能够避免程序员,设计师以及美术人员手足无措地向设计师、制作人询问自己的工作职 责这种无序状态。设计文件让他们不再局限于一个狭小空间编制程序或制作动画,而是让他们真正清楚该如何将自己的工作与其他人的工作有效地整合在一起。如此便大大减少了 不必要的投入并避免各种混乱。 对于团队中的不同角色来说,文件的含义也不同。对于制作人来说,设计文件是他“布道”的圣经;如果制作人不能认同设计文件或者不能让团队成员理念文件,那么它就失去了 原有的价值。对于设计师来说,文件是一种传达制作人理念的方法,能够告知他们更多关于游戏执行的细节内容。首席设计师可以说是所有文件的作者——除了技术说明,因为这 是高级程序员或技术总监所撰写的。而对于程序员和美术人员来说,设计文件则是他们的执行指令,也是他们表现自己设计,美工以及编码技能的重要方式。设计文件应该是团队 共同努力的结晶,因为几乎团队中的所有人都会玩游戏,并都将为游戏设计做出自己的贡献。 设计文件也不会取代设计会议或电子讨论会议。在撰写出文件之前让所有人聚集在会议室中进行讨论,或者根据每个人的观点做出总结性规划都是决定游戏内容的最快速方法。设 计文件只能够表达出一致意见,具体化各种观点并消除模糊性。但是它本身也只是讨论的一部分内容。尽管设计文件的宗旨是巩固想法和计划,但它们也并非板上钉钉的内容。应 该允许团队成员编辑文件内容或发表评论,让大家更好地交换彼此的意见。 明确文件设计大纲的益处 遵从明确的设计原则将能够让你的所有项目受益。因为这类大纲有助于开发者摆脱华而不实的内容,让所有成员更加明确自己的任务,并确保你的项目能够遵循一定的规程,从而 助你更加轻松地安排工作并执行测试计划。 减少华而不实的内容。大纲通过要求设计师确定游戏中的实质元素并减少那些不切合时机的白日梦,从而让他们能够投入那些更加切实可行的任务中。 清晰性和确定性。大纲能够进一步保证设计过程中的清晰性和确定性。它创造出了一种一致性,让读者能够更容易理解文件内容。并且也让作者从读者角度出发,撰写更加通俗易 懂的内容。 大纲可以确保特定的流程遵从设计文件的安排——这些安排包括市场研究,技术评估,深入探索以及观点传播的过程。 大纲有助于拟定安排和测试计划。遵循明确大纲的设计文件能够帮助你更快速地落实行动。文件中明确列出了美术人员和作曲人员所需要创作的图像和声音要求;帮助关卡设计师 有序地分解了故事中的不同关卡,并罗列出了要求数据输入和脚本撰写的游戏对象;确定了程序员所需负责的不同程序领域和规程;最后,它还明确了QA团队在测试计划中需要重 视的各种游戏元素,特征和功能等内容。 大纲会发生变化。基于项目的独特性,你有可能需要放弃一定的原则转而遵循其它内容。例如移植项目通常都比较简单,除了技术说明之外它们并不会要求额外的文件内容(除非 改变了原先的设计)。续集游戏(游戏邦注:如《银河飞将II》,《银河飞将III》等)以及其它非常有名的设计(如《大富翁》或扑克游戏)便不需要过多地解释相关机制内容, 而是应该提供给读者们关于现有游戏或设计的相关文件。只有一些具体的特殊执行项目需要提供明确的文件。 游戏理念大纲 游戏理念大纲能够传达游戏的核心理念。通常这只要1至2页的文件描述,因为简洁的表达才能够鼓励更多创造性理念的涌现。游戏理念文件的目标读者应该是那些你希望介绍游戏 的对象,特别是那些能够帮助你在接下来的正式游戏提案中出谋划策的人。 一般来说,所有的理念在传达给产品开发部之前都需要先给开发部主管(或执行制作人)过目。而该主管则需要判断这些理念是否具有价值,是否值得他们投入更多资源落实开发 。 开发主管或许会认可游戏理念,但是他们仍会要求做出一些改变。他们将会与一些设计人员和制作人,甚至整个部门或公司成员分享这些理念;如此汇聚了大量人才的想法和想象 力后,游戏理念必然会变得更具有吸引力。 游戏理念应该包含以下内容: 介绍 背景(非必要选项) 描述 主要功能 类型 平台 概念艺术(非必要选项) 介绍:游戏理念中的介绍包含了文件中一些最重要的关键字——能够帮助读者更好地理解文件内容。尝试着将游戏中一些重要内容以一个句子简要地表达出来,包括游戏名称,类 型,方向,设置,差异性,平台以及其它关键内容(差异性是指如何让你的游戏有别于同类型的其它游戏)例如: “《Man or Machine》是一款PC平台上的第一人称射击游戏,游戏使用《Quake II》引擎将玩家带进了37世纪的高科技星际战争中,他们将在此扮演一个机器人太空战士的角色。 ” 用几个句子描写介绍能够更加清晰地向读者解说内容。但是你同时也需要记住,如果你介绍的内容越繁琐,读者便很容易觉得你的观点不具有说服力。 背景(非必要选项):游戏理念的背景内容与你在介绍中所提到的产品,项目,授权或者其它属性相关。本质上来看,背景是独立于介绍内容,所以如果读者已经拥有了相关的背 景知识便可以轻易跳过它。不过对于那些授权游戏,续集游戏或者深受早前相同类型影响的游戏,背景尤为重要。如果你想要使用现有代码,工具或授权使用一个游戏引擎,你就 需要在背景中描写清楚这些内容以及它们的优势。 描述:通过使用几个段落或者一页的空间,将读者当成玩家对他们阐述你的游戏。你需要以第二人称的表达方法——“你”进行描述,并努力让这部分内容成为让玩家兴奋的叙述 体验。在此,你可以通过描写玩家该做些什么或者能够看到些什么而向他们传达核心游戏玩法;避免一些细节描述,如点击鼠标或击键,但是也不能太过含糊。你希望读者们都能 融入游戏角色中。同时你需要将细节关卡适当地安置在GUI互动上。你的表达方式应该像“查看你的战术雷达并捕捉更多靠近你的妖怪”,而不是“你应该点击战术雷达按钮,随后 会挑出一个窗口告知你有两个妖怪正在逼近你。”你必须利用描述内容有效且清晰地呈现出游戏内容和娱乐价值。 主要特色:游戏理念的主要特色就像是一个项目清单,能够帮助你的游戏区别于其它游戏,并为后来的文件明确方向。这是对于描述阶段所提到的功能的总结。而这些项目内容将 最终出现在游戏包装背面或促销单上,并且同时也将包含一些延伸内容。例如: “高级人工智能(AI):《Man or Machine》将使当年《半条命》中富有挑战性和真实感的AI实现更大的飞跃。” 判断该罗列出多少特色也需要仔细掂量。如果你面对的是比益智游戏更复杂的游戏,那么只罗列出1、2个主要特色便不是明确的决策;相反地,如果你的特色超过1页篇幅,玩家便 会感觉自己好像面临非常艰巨的任务,并因此感到胆怯。总之,罗列出过少特色便不能很好地传达你的理念,而滔滔不绝的内容也会冲淡游戏特色的价值。 要切记,不要列出那些众所周知的特色,如“炫目的图像”或“动人的音乐”等,除非你真的认为这些特色远远超越其它竞争对手。华丽的图像以及吸引人的音乐等都是人们对每 一个游戏项目的默认目标。但是,如果你的游戏真的拥有独特的图像或音乐并且能它脱颖而出,那你就应该明确地指出这一点。 类型:也就是定义游戏的类型。以来自杂志或者获奖游戏类别为向导。例如,你可以从如下游戏类型中做出选择:运动类,即时策略,第一人称射击,益智,赛车模拟,冒险,角 色扮演,飞行模拟,竞速射击,模拟上帝,策略,行动策略,回合制策略,卷轴射击,教育类或飞行射击游戏等。然后你可以根据这些名称或重新使用其它短语定义游戏,如现代 ,二战,现实交替,后启示录,未来主义,科幻,幻想,中世纪,古老,太空,网络朋克等。 平台:也就是列出目标平台。如果你认为游戏理念同时适合多个平台,你也应该明确那个属于优先平台。如果你希望创造的是在线多人游戏模式,你也需要注明。 概念艺术(非必要选项):采用一定的美术元素能够帮助你更好地传达理念,并让读者以更加积极的心态感受你的游戏。使用美术去传达独特或复杂的理念。屏幕模型能够帮助你 有效地传达各种想法。但是因为游戏概念艺术超出了许多开发人员的能力范围,如此便可能导致他们所提交的创造理念大大减少;所以这是一种可选择的项目。如果你确定一个理 念具有价值,那就可以从其他技术资源中提取其美术元素。通常,来自于早前项目或者网上的美术内容都有助为文件增色。但要注意避免版权问题。 常见错误 以下是开发者在创造游戏理念时最常遇到的问题: 理念完全不符合公司当前的规划。如果你不想浪费时间去撰写一些矛盾的理念,你就需要好好寻找真正适合自己公司的理念,并学会判断哪些哪些想法才是真正有帮助的。 从资源上来看,文件中的某些要求总是背离现实。你需要尽可能将自己的理念保持在适度范围内;通过使用现有的工具或属性控制预算。确保你能够在特定时间以及合理预算范围 内实践想法。将你的实验技术限制在一个特定区域内;最好不要轻易尝试具有变革性的AI以及最先进的3D引擎。如果你正在创造自己的游戏理念,你就必须先明确时间安排和预期 预算。 文件缺少内容。就像是“《命令与征服》结合《机甲战士》,你命令自己的‘Mech加入战斗,’”但是这种表达却远远不够充分。你的描述必须解释清楚玩家应该执行何种行动, 从而让他们能够对此感兴趣。优秀的描述应该是:“你命令自己的Mech直接朝着Clan MadCat OmniMech暴露的躯壳射击。”这样的描述内容才能消除玩家对于核心游戏玩法的误解 。 游戏并不有趣。一个真正有效的方法便是分解所有玩家可能执行的动词(游戏邦注:包括射击,命令,奔跑,购买,构建以及观看等)并想象玩家是如何执行每个动词。随后,基 于每个动词询问自己这是否有趣;然后问自己目标玩家是否会觉得有趣。你必须确保自己足够客观地回答这些问题。如果你认为玩家所采取的行动不够有趣,你就应该立即为其设 定其它更加有趣的行动。 使用了拙劣的语言和语法表达。你应该仔细检查语法和拼写,避免出现一些不雅或具有诽谤性的言语。因为你并不知道谁最终将阅读你的文件,所以你很难判断某些特别表达的单 词是否会侵犯读者。不论是带有大男子主义,歪曲的政治立场,文化冲突等元素的表达,还是你在午餐时间所开的一个低俗笑话都不应该出现在文件中的。 设计师放弃表达理念。千万不要放弃提交更多创意理念,因为你永远不知道哪个理念才能真正创造出成功的游戏。相信我,坚持总是会有回报的。 游戏提案 游戏提案是用于明确游戏开发项目所需要的资金和资源的正式项目提案。你需要投入一定的时间(当然还有金钱)才能创造出合理的游戏提案,并且它却只针对于那些具有发展前 景的游戏理念。 游戏提案是游戏理念的延伸。撰写游戏提案也需要包含来自于其它部门的反馈和信息,特别是来自于市场营销部门(如果存在的话)的信息。你的市场营销部门必须能够针对于游 戏理念进行一定的市场研究和分析。而如果你的游戏是授权产品,那么财务和法律部门就需要出面审查许可证的可用性以及其中所需要的成本。 程序员,特别是高级程序员或技术总监,应该执行理念的最初技术评估。他们应该评估理念的技术可行性以及那些需要深入研究的程序编制领域。他们应该评估项目的风险以及主 要任务,并制定相关策略或找出替代选择。同时他们也需要粗略评估研究与开发所需要的时间和资源。 游戏提案中应该包含游戏理念的修订版本。关于理念文件的技术,市场营销以及财务反馈都将要求你适当压缩理念内容;但同时你也可能需要修改并添加其它功能。并且你需要确 保这种改变不会让任何人感到惊讶,因为这是理念首次接受批评与协作讨论的过程。在正式创造出游戏提案之前将相关反馈和分析副本提交给开发总监(或其他要求审查游戏提案 的人士)过目;这不仅能够让一些特定人士或部门给予理念相应的书面评价,同时也给予了总监否决,修改或主张其它提案的权利。 游戏提案包含以下内容: 修订后的游戏理念(前序要素) 市场分析 技术分析 法律分析(如果可行的话) 成本和收益预测 美术 市场分析:市场营销部门或者市场研究公司(如果你的公司支付得起这笔费用)应该编辑这些信息。而如果你是自己进行编辑,你就应该竭力避免乱猜数字的可能性。在网络上寻 找信息,并基于现有同类型游戏的点击数研究它们的市场表现。 目标市场:目标市场是基于游戏类型和平台进行定义,在理念文件中已经相应地处理了这些问题。你可以根据一些已经成功占领市场的特定游戏进一步分析这一定义。最成功的游 戏总是能够预测市场的发展潜能以及规模;并且你也能够因此了解到典型的用户年龄范围,性别以及其它重要的市场用户特征。而如果你的游戏包含有授权属性或者属于续集游戏 ,你就有必要描述原有市场情况。 表现最佳者:列出市场中的表现最佳的游戏。你应该指出它们的销量,获得突破的数据以及取得成功的续集作品。同时还应明确它们的发行日期;但是不需要过于精确标注出来, 就像1998年第一季度或1998年春天如此即可。在这种研究过程中我们可能需要追溯到早前的一些信息,所以你最好能够按照时间顺序罗列这些数据。 列出这些游戏所属平台(如果这些游戏所在平台,与提案游戏不同)。因为平台的改变也会引起市场变化,所以你应该始终罗列出目标平台上一些相同类型的游戏,即使它们的市 场表现不如其它游戏;因为这些数据能够提醒你某种特殊类型游戏在某一平台上的发展较为萧条。例如,回合制策略游戏在PC平台上具有非常好的销量,但是在索尼的PlayStation 上却成绩惨淡。所以如果你面对的是回合制策略游戏,你就应该在最佳表现者的列表上同时呈现出糟糕表现者的情况。 比较特色:分解这些最佳表现者的卖点,将其与理念文件中的主要特色进行比较;并尝试着提供一些细节描写。举个例子来说,如在《命令与征服》,《黑暗王朝》以及《神话》 中的策略战斗中,你将出于某种优势而命令自己的单位去攻击特定的目标并将其移动到特殊位置或范围内。玩家在游戏过程中将会发现大多数单位的独特优势和劣势,并因此备受 鼓励而创造出超级战术。Tanktics》中拥有各种类型的命令,让玩家能够在此执行超级战术,如捕获,撞击以及击跑配合等。而因为游戏中的地形,移动以及奖励范围;射击弧 以及后击和侧击位置的弱点使单位位置的设置和目标的选择变得更加重要。所有的单位都拥有不同的武器,装甲以及速度,以此能够区别它们的优劣势并鼓励玩家制定战术。随着 时间的流逝,你不仅能够精通这些战术,你也能够根据自己的命令而编写策略脚本了。 技术分析:技术分析一般是由经验丰富的程序设计员执笔,如果是技术总监或者首席程序员便再好不过;随后再进行编辑而成为最终的提案。提案评论者将使用这些技术分析做出 决策。并且老实说,技术分析还能够让评论者更加乐观地面对游戏机遇。 实验性功能:明确设计中那些具有实验性的功能,即未经实验或未经证明的技术,方法,看法或其它独特的理念。排除那些已经在现有游戏中得到证实的功能,即使它们对于你们 的开发团队来说还很陌生。例如,即使团队从未开发过3D引擎,也不能轻易将其当成实验性功能;而是应该将其归为技术分析内容中一个或多个类别中。另一方面,如果你的开发 团队正在使用quads体系开发3D引擎,那么你便能够将这种体验记录在实验性功能列表中。 估计实验性功能达到评价状态需要多长时间,以及完成整个功能又需要多长时间。一般来说,你的安排列表中总需要为实验性领域挪出更多时间,所以如果你罗列出更多实验性功 能,你就需要投入更长的时间。尽管很多公司都尽量回避那些耗时18至24个月的游戏项目,但是也有很多开发者意识到,如果要开发一款具有领先优势的游戏,这种实验值得一试 。 主要开发任务:通过一个段落或者一些项目符号明确列出主要的开发任务,并使用普通人也能够理解的非技术类语言。“主要”主要指开发月数。你需要假设你拥有开发所需要的 所有资源,而因此估计你完成该任务需要多少时间。你同样也可以估计你所需要的资源。例如:“人工智能脚本解析器:需要两个程序设计员花费3至4个月的时间。解析器将阅读 并以较低级别的逻辑编辑AI脚本,并基于运行时间做出指示。” 风险:列出任何技术风险。如果你不能预见任何技术风险,请务必说出来。风险是指研究开发过程中因为失败而造成的挫折(引起工作延误数周或数月)。记录下技术——尽管这 些技术可能已经得到竞争者的成功证实,但是你们公司却从未尝试过或者说对此没有任何经验。例如,如果你的公司从未开发过一款即时策略游戏,那就记录下即时策略内容;或 者如果你们公司首次接触3D,那就记录下3D渲染技术等。记录下之前提过的任何主要开发任务——如果你察觉到其中的风险。同时,所有未经实验的解决方法(游戏邦注:包括3D 引擎,编辑器,代码库,API以及驱动器等)也应该被当成是风险而记录下来,因为这些方法可能最终也不会满足你的特殊需求。记录下任何经由外部承包商进行的开发工作,因为 通常来说这种行为总是具有较大风险。当你在评估风险的同时,你也应该清楚修改或替换这些风险技术会带来何种影响。以周或月为单位指示发行日期。记录下时间对于任何特殊 资源的影响。记录下任何能够修改风险的新资源(包括人力,软件,硬件等)。虽然这个阶段看起来很繁琐,但是它却能够为你的文件评论者创造一个舒适的阅读环境,即他们将 会认为游戏执行始终处于适当的控制之下(特别是当他们自己也能够察觉到风险的存在时)。除此之外,你还能够有理地说道:“你可别说我没有警告你”之类的话。 替代性选择(如果有的话):替代选择是你围绕着这些实验性或风险性功能,以及致力于主要开发任务时所必需的元素。通过明确替代选择,有助于文件阅读者自己做出选择。例 如列出任何需要耗费更多时间和金钱但却能够获得更好结果的选择,或者相反的内容(花费更少的时间和金钱但是结果却不如预期那般令人满意)。不管你给予何种选择,都需要 明确说明它们的优劣。 估计资源:记录下估计资源:员工,承包商,软件以及硬件等等。对于公司外部人员(如那些也有可能阅读文件的发行商或投资者)则使用一般的产业标准模式。以月或周为单位 记录下所需要的时间。此时无需考虑实际成本(以美元为单位),因为这是我们在之后才需要明确的内容。 估计时间表:时间表是遵循我们的里程表估算的全面开发周期,即从最早的起始日期开始,然后经历开端,测试以及正式发行。 法律分析(如果有的话):如果你的游戏涉及版权,商标,特许权协议或者其它牵扯到费用,诉讼成本,版权声明或者限制条件的合同问题,请务必在此罗列出来。并且无需提及 游戏名称或logo版权的必要性,因为这都是众所周知的内容。 成本和收益预测:与财务和采购部门协作进行成本和收益的预测。这些数据应该让读者们能够基于技术分析所估算的资源大概清楚资源所需成本。 资源成本:资源成本是基于技术分析所估算的资源。就像员工成本将基于工资和日常开支,而这也是财务或工资管理部门应该提供的数据。你可以通过名称或标准去记录这些平均 数值。同时,你也应该记录下你所购买的任何软件或硬件,即使你将在其它项目中使用这些资源或者它们将被整合进日常开支预算中。使用表格或嵌入式表格以帮助你更加轻松地 进行编辑,并让读者更加清晰地进行阅读。如下图:  table(from gamasutra)

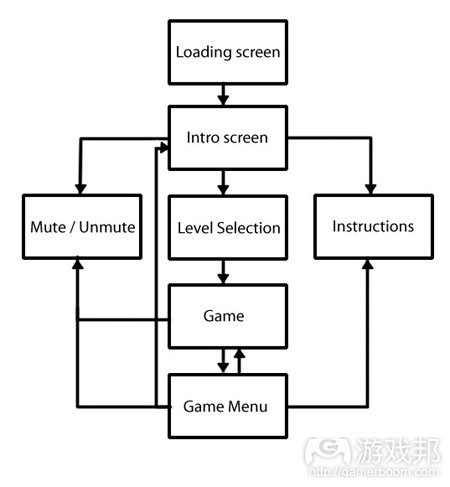

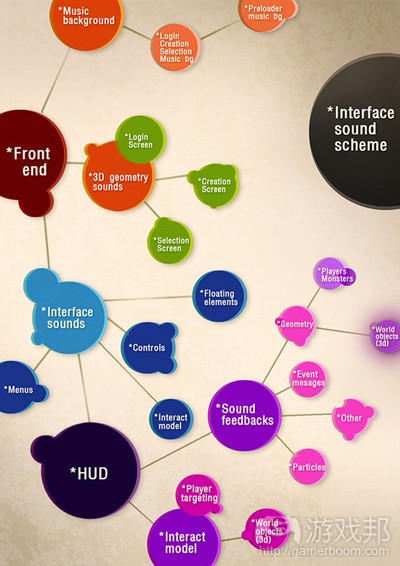

追加成本(如果有的话):这是指估算授权,承包,外包测试等产生的额外费用。 建议零售价(SRP):你应该在你的游戏沦为讨价还价牺牲品之前明确一个建议零售价。建议零售价应该基于现有游戏的价格,并评估游戏开发的总体价值以及生产开发成本等。当 然了,发行商总是想要压低游戏的定价,或者通过各种促销方法进一步压低游戏价格,不过这些方法最终也能帮助你的游戏取得不错成绩。因为你需要牢记,越高的定价也就意味 着越低的销量,特别是当你面对的是市场上竞争激烈的游戏类型(即供过于求)时。 收益预测:你应该根据自己所罗列出的成本以及建议零售价而呈现出悲观,预期以及乐观三种销量值。而市场营销或者公司日常开支等元素则不包含在此范围中,因为这些内容都 属于可变化的内容;但是如果你知道最低市场营销预算值,你就应该将其涵括在考虑范围内。通常情况下,圆形分格统计图表或者长条图都非常适合呈现收益预测数据。除此之外 ,你还应该呈现出技术评估所描写的风险成本,以及使用或不使用风险评估的预期总值。 美术:如果你的游戏理念中未包含任何美术内容,那么你的游戏提案中就不能缺少这些内容。美术内容必须由熟练的设计师所创造,所以你应该删除或替换掉理念文件中那些非设 计师创造的美术内容。美术能够明确游戏基调。如果你的读者只是根据美术效果去评估提案,你就需要确保在美术内容中展现出游戏的风格和目的。美术内容包括彩色或黑白的角 色,单位,建筑,武器示意图;动作动画;并且如果你的游戏是驾驶模拟游戏,也可以包含GUI实物模型等。确保你拥有精致的封面图像。在文件页面中张贴图像能够为你的文件加 分,并更好地引起读者的兴趣。 描述:整份提案文件应该包含改订过的理念文件,印刷成册并与美术副本一起装订在特定的报告文件夹中。你应该将这份文件呈现给那些前来你的办公室拜访的商务人士。你应该 始终牢记你需要一大笔的投资,所以要尽可能让你的提案看起来更加吸引人,从而能够吸引投资者的注意。用某些程序(如微软的Persuasion)播放灯片能够帮助你更好地阐述关 键点并呈现美术内容。 常见问题 准备游戏提案时常常出现的一些问题是: 用一些没有根据的数字进行分析。通过罗列资源或者解释你如何获得这些数据进行证实。如果制作人凭空捏造一些数字并将其用于文件中,读者便不会信任并阅读他的文件。 提案太过乏味。这是一份有关销售的文件,所以不要让你的读者感到无聊。将事实呈现给他们,并且确保这些事实足够有趣,简洁且有说服力。 提案不能提前解决一些常见的问题。你应该清楚你的提案真正面临的是什么——其它提案,竞争产品,财务问题,成本和时间预期值,游戏偏见以及历史灾难等问题。而如果你能 够先发制人地解决这些问题而不是留到评论过程中等待评论者逐步挖掘,你的提案便有可能获得认可。 提案作者对于批评总是太过敏感。不要惊讶你的游戏提案发起人提出一些完全相反的观点。你需要做的只是保证提案的一致性,相信它并保持自信,如此你才能经受各种批评的挑 战,并让支持者始终站在你这边。 提案作者过于刻板而不愿意改变游戏。通常在收集研究或接受来自评审委员会的批评意见时,你会发现一些需要你改变游戏或压缩设计的合理建议。游戏开发是一个相互合作的过 程。你应该接受反馈并改变设计,否则你的游戏将只会止步不前;并且只有这样你的游戏才能保持活力并持续发展。 功能 vs 技术说明文件 游戏行业传统上只有一种说明文件,涉及多少技术内容主要取决于文件撰写人的意愿。而程序员之后所写的用于执行过程的文件,一般都是非正式内容,通常写在白板或记事本上 。但为了确保项目执行顺畅,按期交付并且不超出预算,这种项目说明文件就应该包含更多技术内容。制作如此详细的技术说明文件需花费一些时间——而如果产品目标和功能发 生变化,或者未通过批准,那么这些时间就白费了。 但随着更多富有经验的程序员和软件开发项目经理加入游戏行业,这个问题也得到了妥善解决。这些人才引进了新的文件设计标准,确保项目规划更明确,并减少了技术性问题。 他们将设计文件按照目标、方法、功能和技术类别,将其划分为功能说明文件和技术说明文件。这样产品客户、用户或主设计师就可以浏览功能规范书,直接反馈是否赞同指定软 件的目标和功能,而无需考虑将由程序员等人员来处理的技术性决策和文件。 因此,技术人员需等到功能说明文件通过审核并签收之后,才开始制作技术规格书。他们无需理会功能文件签收之后的任何设计变化,除非该文件更新并制定出新规划。这样就可 以节省程序员的时间,让他们更好把握自己的工作安排,专注于解决执行过程中的开发方法和技术问题。 不过也有许多公司至今仍将功能规范书称为“设计文件”,但同时也会制作技术说明文件。 游戏中包含哪些内容及其用途都是功能规范书所涵盖的内容。其中包含内容通常取决于撰写者的立场和想法。而如何执行及其运行这些功能则是技术规格书的内容(游戏邦注:其 撰写原则主要取决于系统角度)。这两者都是游戏开发过程中设计阶段的重要环节。 功能规范书撰写原则 功能规范书(以下简称规范书)是产品功能及特色的概括。其瞄准的读者则是执行这些工作的团队,以及负责审核游戏设计的人员。规范书是游戏理念、评论及讨论的顶点,它是 游戏理念大纲及项目提案所描述愿景的具体化版本,它是技术规格书、项目进程安排和执行的起点。 必须从用户角度撰写其中所有内容。换句话说,这个文件中要描述的重点就是用户所看到、所经验或接触的内容。人们总是易于将其制作成以系统为导向的文件(尤其是程序员) ,但这些抽象内容非常不利于目标读者阅读和理解。读者只希望通过这份文件想象游戏中发生的情况,而不是其运行原理。 这种规范书可能短至10页,也可能长达数百页,其长短要取决于游戏系统的复杂性。但一定不能指望一页纸就了事。我曾见过不少非常出色的设计文件,有些不足50页而有些却更 为冗长,重要的是内容明确而非篇幅长短。 这类文件的撰写时长也不尽相同,如果是益智游戏可能几天就足矣,射击游戏游戏是一个月,而RPG或策略游戏等更复杂的项目可能长达数月。需注意,文件撰写时长与其篇幅长短 未必成正比。造成这种情况的原因包括考虑时间长短不同,当游戏拥有独一无二、原创的特性,或者玩法极具深度时更是如此。当然,主设计师制定决策的效率也会对文件撰写时 长造成影响,尤其是当大家对这个游戏项目都很有想法和激情的时候。 对多数人来说,这个功能规范书就是设计文件的开端。他们可以直接跳过概念文件和项目提纳中的市场调研和评审阶段(游戏邦注:这方面内容旨在锁定项目愿景和目标市场)。 游戏首席设计师通常就是功能规范书的撰写人。这份文件可能是集体智慧的结晶,也可能只是落实到书面上的制作人项目愿意。有时候制作人也会自己动手完成这个文件,这就可 以确保文件表达的正是其本人的想法。与打电话游戏一样,在撰写这种文件的时候,项目负责人所表达的想法可能与后来写在书面上的内容存在出入。无论是哪种撰写过程,或者 由谁负责撰写文件,重要的是制作人和首席设计师对这个文件达成了一致意见。不可出现口头所说与纸上所写内容相左,或者完全无视文件内容的情况。 我还没见过不会在执行过程中发生变化的设计,重要的是针对文件内容进行沟通和交流,即使需要更改或添加内容也不例外。有些变动由于时间有限,需要立即处理,这样才能让 文件清晰明了。即使这些变动只是写在电子备忘录或者纸张上,也要确保将其添加到未来的规范文件中。但如果游戏版本发生变化,最好从一个新理念大纲和项目提议重新开始入 手。更新版文件的准确性有利于节省未来的大量时间。 另一方面,这个文件不能出现太多技术倾向,因为它的读者基本上不是程序员。如果你发现它出现技术倾向,那就要收手了,因为这是技术规格书所写的内容,否则就会让非技术 读者像看天书一样不知所云。与此同理,你或者其他撰写者可能也未必是技术人员,所以无权通过这份文件指令程序员如何执行工作。这要让他们在书写技术规格书时自己决定。 毕竟这个文件纯粹是用于交流和审核产品内容,而非指导如何完成任务。但你可以针对自己认为非常重要的地方进行一些简短描述。例如,你不能指令使用哪些变量,以及如何使 用这些变量去模拟一个物理定律,但你可以指出与这个物理公式有关的因素。同理,你不应该告诉程序员如何定义他们的数据结构和对象,但可以针对数据输入界面和数据描述提 出一些建议。 功能规范书可以划分为以下6个主要版块: *游戏机制 *用户界面 *美术和视频 *声音和音乐 *故事(视情况而定) *关卡需求 游戏机制 游戏机制要以详细术语描述游戏玩法,它始于核心玩法,其次是追随玩家游戏活动的游戏流程。剩下的都属于无限的细节内容。 核心玩法:要用数个段落描述游戏本质。这些文字好比是设计发芽的种子,将其植入一个已知市场的土壤,它们就会开始生根,牢牢把握目标愿景,以繁衍出成功的游戏。这与游 戏理念大纲中的描述版块内容相似,但它属于非故事内容,并且其要点描述更明确,但这一点主要取决于不同游戏类型的要求。 游戏流程:对玩家活动进行详细描述,注意玩家在这一过程中的挑战性和娱乐性的发展。如果说核心玩法是大树的根,那么游戏流程就是树干和分枝,所有游戏活动都是从核心玩 法扩展而来。要明确指出玩家所执行操作,尽量使用“射击”、“指挥”、“选择”和“移动”等准确的词语而非“点击”、“摁压”和“拖拽”等字眼来描述内容。因为这种描 述差异可能会对GUI运行方式产生影响。如果你在此首次提到屏幕、窗口或指令条等GUI元素,那就要记得将读者引向“用户界面”版块的内容。 角色/单位(视情况而定):它们是在游戏中受玩家或AI控制的演员。这里应包含一个简短描述和一些合适的数值。这些数值需划分成A到Z或者“高到低”等级,这样才能明确每个 单位彼此间的地位。但此时不宜插入准确数据,因为程序员到时候自然会在技术规格书中提到这一点,并创建一个可让你试验这些数值的环境。除了数值之外,这里还要列出单位 的特殊技能或能力,并进行简要描述,但如果这些内容很复杂,可以在“玩法元素”版块进行扩展。 玩法元素:这是针对玩家(或者角色/单位)所能接触或获取的所有元素的功能描述。其内容包括武器、建筑、转换器、升降机、陷阱、道具、咒语、升级能量和特殊技能等。在描 述每个种类特点之前,要用一段话指明这些元素的引进或交互方式。 游戏物理和数值:要划分游戏中的物理元素,例如移动、爆炸、战斗等,将每个种类分成一个子集。根据分配给角色、单位和玩法元素的数值来描述这些物理内容的外观和感觉。 要指出催生这些物理功能所需的数值。描写这部分内容时要征求程序员的看法,例如游戏如何处理这些物理内容,数量如何严重影响玩家表现等问题。 这里的内容可能有点枯燥,但切记不可过于技术化。不要使用确切的数字或编程术语。因为这些都是程序员之后撰写技术规格书所考虑的内容。只要告诉他们你希望获得什么效果 即可。例如,“这些单位上坡时会减速,下坡时会加速,除非它们是滑翔或飞行工具。攀升和加速的数值,以及倾斜角度会影响它们的表现。”你不可告诉程序员应该使用哪种算 法调整速度,因为你自己并非程序员,他们才是这方面的行家。 人工智能(视情况而定):这里要描述游戏AI的理想行为和可用性。其中包括移动(寻径),反应、触发器、目标选择,其他作战决策(游戏邦注:例如射程、定位等),以及与 玩法元素的互动。要描述关卡设计师控制AI的路径,例如使用.INI文件,包含游戏数值或C代码的文件,专用AI脚本等。 多人模式(视情况而定):要指明多人玩法模式(例如:贴身肉博战、合作对付AI、团队等),以及在不同网络中这种模式所支持的玩家人数。要描述多人模式与单人模式在游戏 流程、角色/单位、玩法元素和AI上的区别。 用户界面 因为界面变动很频繁,所以我们看似没必要将其列入文件。但是,我们将其组织到文件中,就可以最小化设计变动所造成的影响。这里的内容包括屏幕和窗口导航流程图,所有的 屏幕和窗口功能需求。完成这一步后,GUI美工才可以根据需求自由发挥创意。而在美术动工之前,你得先提供模型。然后描述所有需要编程的CUI对象。  game UI flowchart(from behance.net)

流程图:这是多个屏幕和窗口的导航图表。可以使用VISIO或类似的流程图工具将已标签和标数的方框连接起来,使其代表屏幕、窗口、菜单等元素。要记得在每个表格的角落列出 所有项目的序号,以方便程序员理解和落实工作。 功能需求:这是每个屏幕、窗口以及菜单的功能分解,它应列出用户操作及预期结果,可能还会包含图表和模型。可以适当列出一些具体交互行为(例如按钮、点击、拖放和产生 动画),但最好不要在此添加过多这种内容,因为这会涉及到执行方式。当然,如果点击按钮这种描述更易理解,或者真的很有必要指出某物的特定运行方式,那就要详细指出其 交互方式。 模型:针对所有屏幕、窗口和菜单创建模型。这一点通常被人所忽视,但如果美工对其工作没有概念,就可以利用模型启发他们。不要费太多时间创建精美的模型,只要用一些文 本标签画些简单的线条即可。没有必要上色,因为这可能弄巧成拙,除非颜色真的很重要。可以利用一些绘图软件提供的模板快速建模。 GUI对象:这是创建所有屏幕、窗口和菜单的基本模块。这里并不包括主视图入口的项目,因为它们会出现这后的美术列表中。罗列在此的GUI对象主要用于帮助程序员了解自己需 要编辑的内容。你应该详细说明这些模块的交互方式。虽然这看似不值一提的内容,但结合技术规格书与项目安排来考虑事情,无疑更有助于了解项目整体需求。 有些游戏很容易整合GUI对象列表中的按钮、图标、指针、滑块、HUD元素等内容,但界面截然不同的游戏则未必如此。但无论如何,对象之间的交互方式不会有太大出入,毕竟按 钮就是按钮,点击女妖的头部与点击灰色矩形并无区别。 美术和视频 这里就需要列出游戏中的所有美术和视频内容。可以添加一些占位符参照内容以便之后命名,例如特定任务的美术内容,用于营销材料、样本、网页、手册和包装的美术内容。 总体目标:在这里你要将图案、特点、风格、基调、色彩等与美术目标有关的内容描述清楚。要确保主要美术设计人员和美术总监与项目总监或制作人达成一致意见。这样就可以 节省下日后的返功时间。 2D美术&动画:这真是一个足以纳入美术工作安排的大型内容列表,必要的话也可以加入描述内容。有些美术内容需要额外说明,而有些可能有特殊的设计要求,这些都要一一说明 。可以将美术内容划分为多个版块。主设计人员可能有一些自己喜欢的安排方式。以下是我列出的这些典型版块内容: *GUI:屏幕、窗口、指针、标记、图标、按钮、菜单、外形等。 *营销及包装美术设计:你在这里和美术工作安排中可能都要考虑到这一点,其中包括网页美术设计、销售传单设计、样本启动画面、杂志等平面媒体以及包装合、手册中的美术设 计。 *地形:例如区块、纹理、地势目标和背景等场景美术。 *玩法元素:玩家和敌人动画(精灵或模型)、玩法结构和互动物体、武器、升级道具等。不要忘了还有受伤状态。 *特效:喝彩、爆炸、火花、足迹、血迹、碎片、残骸等。 3D美术&动画:这里的需求和用途与2D美术列表相同。其中差别可能就在于任务分工不同。美术团队通常会将3D美术任务并入建模、纹理、动画和特效工作,以便最大化利用成员的 技术,并保持工作一致性。 电影艺术:这通常是指介于不同任务之间,以及出现在游戏尾声的2D或3D场景。这原本应该像电影脚本一样另外撰写一个文件,但这属于制作方面的工作。功能规范书一般也会将 其纳入文件在,列出其一般用途、内容和目标长度。如果涉及相关视频内容,就会将其列入以下的子集。 视频:除非你是制作全动态影象(简称FMV)游戏,否则就没必要在这个子集中投入太多精力。如果你的GUI中有个用来阐述情节内容的视频,就可以将它纳入此列。所有的视频任 务都需要编写脚本,但这属于制作工作。这里也要列出一般用途,预期长度,以及演员数量、场景设计等一般内容,即便它只是个由蓝屏切入3D渲染背景的镜头。 声音和音乐 总体目标:强调声音和音乐的美学和技术目标。描述你所追求的主题或基调,可以列出原有游戏或电影作为参照。要指出技术要求和剪辑目标,例如采样率,磁盘空间,音乐格式 和转换方法。 音效:列出游戏所需要的所有音效及其使用位置。要列出预期的文件名称,但在文件命名规范上要与声音程序员和音效技术人员进行沟通,以便大家快速找到音效文件,并将其运 用到游戏中。 不要忘了所有可能需要使用音效的地方。所以要浏览一遍游戏元素及美术列表,看看还有哪些地方需要添加声音元素,以下就是一些值得考虑的地方: *GUI:点击按钮、打开窗口、确认命令 *特效:武器开火、爆炸、雷达鸣响 *单位/角色:对话录音、跺脚、碰撞等 *玩法元素:拾取物品、警报、环境声效 *地形(环境):鸟声、丛林声、虫鸣声 *移动:风声、脚步声、地板咯吱声、涉水声、踏入泥淖的声音 音乐:列出游戏中的音乐需求及其使用位置。描述音乐基调和其他微妙特点。游戏通常会重复使用一个主题和旋律,要指出需要重用这些主题的地方,并且咨询作曲人的看法。 *事件:成功/失败/死亡/胜利/发现等。 *屏幕:针对开头、鸣谢和结尾屏幕设置的音乐基调。 *关卡主题:针对特定关卡的音乐(由其设计师选择音乐主题)。 *情境:设置不同情境的基调(游戏邦注:例如危险逼近、战斗和探索的时候)。 *电影音轨 故事(视情况而定) 写下游戏所讲述的故事概要,包括背景故事和角色细节描述。要指时游戏文本和对话需求,以便将其添加到项目进程安排中。但也不可过份纠缠于这些细节以至于忽视其他内容, 毕竟讲述故事并非多数游戏的重点。当然,如果你开发的是一款冒险游戏,那就很有必要在此多下一番功夫。 关卡需求 关卡图表:不论这是一个线性活动,拥有分枝的任务树,还是一个自由开放世界,这个图表都应该是所有关卡创建的基础。如果关卡结构仅需一个简单的列表就能表述清楚,就不 需要创建图表了。下图是一个典型的成功/失败分枝任务树图表。当然每款游戏特点不同,其图表结构也会有所差异,重要的是要让它成为有助于关卡设计师和读者理解内容的线路 图。 内容揭露计划表:它应该是一个玩家首次接触游戏时所会看到的游戏内容表格或电子表格。它可以是以关卡为行,以每种内容为列。其中的内容包括升级道具、武器、敌人类型、 诀窍、陷阱、目标类型、挑战、建筑以及其他所有游戏玩法元素。这个表格可确保游戏中的内容,即促使玩家进入下个关卡的元素妥当分配,不会出现超量或没有充分使用的情况 。 如果有些内容已经停用,那就最好将这个计划表绘制为Gannt图,用线条指出可用的内容和资产。这样才好让关卡设计师知道自己该在何处下功夫,这样就不会搞砸自己或其他人的 关卡。 关卡设计核心:在写出详细的设计文件之前,要先点出设计核心。设计师用工具试验并开发了首个可玩关卡之后再推出的设计,更有可能获得成功。所以此时最好先列出每个关卡 的核心,描述关卡目标,玩法以及它如何与故事(如果游戏有故事内容)相结合。可以选择先勾勒一个草图,如果设计师对此已经拥有明确想法那就再好不过了。要确保文件列出 了地形、目标、新揭露的内容,以及目标难度等级等特定的关卡需求。 普遍误区 以下是设计师需要注意的一些普遍问题: *细节不足:要用充分的细节传达关卡目的和功能,避免使用一些含糊不清的字段,除非你补充了更多详情。 *越俎代庖:正如你不应该告诉厨师如何使用沙司调味,你也不可告诉美工如何管理自己的256调色盘,不能教程序员如何定义一个特定的数据结构。只要列出重要的目标愿景即可 ,否则只会浪费彼此的时间,毕竟这种细节更适合出现在程序员所撰写的技术规格书中。 *模糊不清或自相矛盾的内容:要警惕这种情况,因为它会使项目愿景偏离方向,产生一些误解,导致功能规范书失效。 *内容繁冗:这份文件可能没有什么明显错误,没有模糊不清的地方,也没有任何缺乏,但就是内容太多了。在充实这份文件时要把握好执行设计的时长,删减非必要的冗余功能, 可以将其保存起来运用到游戏继作中,或者为保留这些功能而争取推迟项目交付日期。 *过于个人化的设计:我曾经强调过游戏设计是一个协作的过程,虽然大家是各司其职地完成自己的工作,但功能规范书应该是集体智慧的结晶,因此它不可以是一项个人产物。否 则会让人觉得自己与设计过程没多大关系,同时也会让这份文件更像是一份命令和计划。团队成员更乐意阅读大家合力完成的设计文件,这样人们提出批评意见时也主要是针对文 件本身而非作者,这样可以让大家更自在地对文件提出改进意见。 *偏离项目愿景:即使拥有一个良好的理念大纲和项目提案,功能规范书也仍有可能出现一些不同解释内容。创意人员通常都有人马行空的想象力,并且很可能在撰写这一文件时受 到自己当时所玩游戏的影响。 技术规格书撰写原则 如果说功能规范书描述的是产品应该包含哪些内容,那么技术规格书解释的就是如何添加内容。技术规格书是游戏的工作蓝图,其作用是促使程序员将设计师的设想转变为现实, 在这一过程中程序员需吃透游戏该执行哪些内容,如何减少执行/集成中的障碍,如何描述编程区以及任务安排。  Game-Design-Document(from gamedesigndocument.org)

许多公司都会略过这个步骤,因为撰写这种文件极为耗时,而且只有程序员可以从中受益。但撰写这份文件总比因未撰写文件而对错误问题采取补救措施更省时省力。技术规格书 的主要作者是主程序员或技术总监,不过如果可以让负责不同编程区域的程序员分工完成内容,这会提高文件撰写效率。必须采用每个程序员都能理解和入手的编辑格式。 该文件的目标读者是项目主程序员以及公司技术总监。因此它是以系统而非用户角度出发撰写内容,看起来会很枯燥,对制作人和其他非技术人员来说简直像是天书。但制作人要 求撰写这一文件的目的在于,确保技术人员考虑周全,即便制作人本身对此并不了解。对主程序员来说,这是一个组织思维和勾勒项目框架的方法。这种编写文件的过程有助于显 示编程环节中的不确定因素和漏洞,以及功能规范书中的模糊或荒谬之处。 许多出色的技术规格书编写格式与本文描述并不相同。这里的格式主要与功能规范书相对应,以确保覆盖所有的功能规范内容。有时候开发团队也可以出于分工不同,或因为基础 系统组织方式而选择不同编写形式。如果这样的话,我建议他们细读功能规范书的每行文字,并以萤光笔标出相关内容,以免忽略某些内容。毕竟疏漏一个细节可能会令产品、项 目和团队动态产生令人不快的结果。 这些原则不会教你如何执行游戏开发,其假设前提是你已经是一个技术能手,富有经验的游戏程序员,而生手则不应该参与这项任务。我认为优秀的技术规格书应该遵从这些原则 ,它们会要求你定义所有游戏中的最普遍元素。有些原则可能并不适用于你的项目,但每个原则都值得认真考虑,毕竟它可能对你有所启发,而这也正是撰写这份文件的意义之一 。 游戏机制 这当然也是这份文件的组成部分。但在这里你会发现将其与功能规范书中的游戏机制部份一一对应的做法有多荒唐了。因为这份文件应以系统为出发点,而不是以设计师或用户的 角度来写作。开篇要提到的是硬件平台和操作系统,外部供应码对象(例如DLL、EXE、驱动器等),并描述内部生成码对象。然后再区分起源于控制环路的特定游戏代码机制。 平台及操作系统:要指出项目所需的硬件平台、操作系统以及支持版本。对PC/Mac游戏来说,要提到最小系统需求和目标运行设备。如果游戏并非以CD而是以卡盘等形式发售,那 就要提到相应的ROM要求。 外部代码:要描述并非项目团队所开发的所有代码来源和用途。这包括操作系统代码和针对不同游戏平台的预处理工具,驱动器和DirectX等代码库,以及项目所需的3D API,或其 他现成解决方案。 代码对象:分解多种代码对象编码、编译和创建到EXE的用途和范围。如果使用到非进程内或者同进程的代码库(例如DLL),那也要分别进行说明,要说清使用对象实例及其存在 目的。 控制环路:每款游戏都有一个控制环路。要详细说明启动代码、主游戏代码的控制转换过程。说明核心循环的功能名称及其作用,例如碰撞、移动和渲染路径。要解释多线程、驱 动器、DLL和内存管理的使用原因。当然,多线程和内存管理的更多详情应该出现于它们使用最频繁的区域,例如渲染或精灵引擎,声音代码和AI。 这部分内容概括的是支持核心玩法的系统和内在框架,以及功能规范书所描述的游戏流程内容。 游戏对象数据:先仔细阅读功能规范书中关于所有角色/单位的描述,以及游戏玩法元素内容。然后规划并列出所有数据结构,以及能够支持这些描述特点、功能和行为的标识符。 从某种程度上说,只有游戏物理、统计数值和AI部分内容考虑周全并载入文件时才可能做到这一点。在为用户界面或任何包含单位/玩法对象特定数据(游戏邦注:例如图票、HUD 元素、动画或特效参照内容)的区域添加统计数值。 如果使用的是面向对象的编程方法,那就要提供类继承树和每个类的界面属性和功能。描述集合的使用方式。列出可能作为全程变量以增强性能的变量,例如可能在碰撞时、移动 或渲染等重要游戏惯例中命被多次引用的对象变量。需要重申的是,我并非教你如何为游戏编程,只是想让你多考虑其中的普遍技术问题,尤其是与整洁性、多功能化或速度有关 的数据结构优化问题。 数据流:要说明数据如何存储、加载、转换、处理、保存和修复。要为数据输入或处理工具提供参考内容,任何复杂或与用户集中型工具都要分别说明功能和技术规范。 游戏物理和统计数值:这里的内容多而繁杂(例如移动、碰撞和战斗等等),但可能也是最有趣的编写和执行内容。但它的代码可能也是编程中变动最为频繁的内容。设计师喜欢 更改内容,并且通常是在游戏具有一定可玩性时才能决定采用哪个设计。因此你的执行计划应该具有模块化和灵活性。要将控制操作行为的所有元素导入可以在运行时间阅读的数 据文件中,这样可以方便设计师在闲暇时间进行调整,无需介入编程调整过程。这个说明文件应该明确区分代码及其控制数据的组合性和分类。 要定义每个函数或程序,描述它的用途,确定由哪些数值来控制它的行为(如常量、变量等)及其修改方法。这包括列出所有参数的函数原型。如果使用到了函数指标和函数重载

,则需详细说明要使用哪个版本的函数。例如,你可能有多个处理不同单位类型移动过程的函数——其中一个处理着陆移动方式,一个负责空中移动方式,一个负责水中移动等,

可以简要描述函数运行方式。对于复杂的函数,可以使用伪代码去说明编码方式。这一点对于要经常进行数值运算的CPU密集型函数来说尤为重要。要考虑如何对其进行优化以增强

运行性能。也许进行一点位移或者使用宏指令就可以提高运行速度。 人工智能(AI):这个环节通常易于延伸成主要内容,但如果根据项目进程表来安排,又总会削减其中篇幅,仅保留必要内容。这说明设计师对复杂AI的追求有增无减,但由于时

间和资源有限,最后总会让AI变成模拟智能或脚本行为。设计AI方案的时候尤其要注意这个问题。尽量在无需添加大层次的情况下完成功能规范书所描述的行业和决策制定方法, 以免让这一过程呈现不必要的现实主义色彩。在此要运用基本的制作法则,假如可以用更少的成本和时间完成一项工作,那就没有必要投入过多时间和资金把事情复杂化。 当然,这里也需要注意一些例外情况。有时候总有些内容需要更长的创建时间,但完成这些内容有利于节省设计师创建关卡的时间。此外,创建一些更有弹性或强大的内容,也可 以为公司开发其他项目提供宝贵的现成素材,或者让项目更易处理设计变更的问题。所以在制定这种决策之前,要先跟制作人和开发主管讨论可行性。 要确保这里的内容包含功能规范书所提到的AI控制方法,例如它是由数据驱动,还是嵌入编译代码,以及它究竟是一个脚本语言还是一个固定的变量集合,抑或是这两者的合体。 AI内容还应该包括寻径、目标选择、测试和附带相应行为的事件,角色制定的其他决策,与游戏情境相关的单位/智能游戏元素以及单位统计数值。 不要在其中添加驱动AI的实际脚本或数据。因为这是制作团队的工作。只要解释清楚决策和行为起因即可。要区别说明控制行为的统计数值。 多人模式:从多人模式角度来评估执行方案,这一点也非常重要。这部分内容应该分别说明游戏机制中的所有多人模式考虑因素,以及功能规范书中所有与多人模式相关的特定需 求。 在多台PC上的多人模式(不同于共享控制器或hotseat模式)有许多需要解决的独特需求。例如,要考虑游戏支持的是哪种连网方式和网络协议?它是基于客户端服务器还是对等网 络?数据包大小是多少,发送频率又如何?数据包结构是什么?如何解决数据包丢失和延迟的问题?要向特定主机传送什么信息?共有多少不同信息,它们何时使用? 用户界面 外观和风格是开发过程中最常变化的设计内容。因此,针对GUI的编程很有必要保持灵活性,要将玩法用途与GUI功能相分离,这样用户交互方法的改变就不会影响到游戏的其他层 面,或者产生重大的改编程序。要使用继承类创建多种GUI对象(控制方法)以保持代码界面在事件中的一致性和数值。这样就可以在无需重大改变调用函数的情况下,将滑动块变 换为文本框或按钮。最好将任何GUI对象都设置为可更改状态。 为此,你的文件应该具有弹性和通用性。需要将GUI划分为屏幕、窗口和菜单分别说明,但不可以延伸至特定交互方法,只需写下不同GUI对象运行方式,使用位置即可。 可以引用之前章节所记录的游戏机制功能,但与界面有关的所有信息都要写在这部分内容中。有关图像引擎的绘图和剪辑路径的内容应该纳入美术和视频章节,但如果涉及视察窗 口和HUD附件,以及玩家交互活动的信息就要引用这里的内容。 要列出所有的全程变量、常量、宏指令、函数名或界面属性,这样程序员就知道如何快速引用文件。这也可以避免重复和不一致性问题。 游戏外壳:列出所有组成游戏外观的屏幕——这包括主游戏屏幕之外的所有屏幕及窗口。它们是由功能规范书中的流程图衍生而来,但可能包括一些主设计师所疏忽的额外屏幕( 例如安装或设置屏幕)。所列的每个项目都要纳入其应用的片段,并描述其用途和范围(例如是在特定关卡数据加载之前还是之后),它将访问和设置的相关数值,它将调用的函 数等。 主游戏屏幕:游戏中可能会有一个或更多与核心游戏玩法有关的屏幕。虽然许多人习惯从GUI角度再到其中复杂性进行考虑,但撰写本文件时要从低级别机制着手,然后再延伸至 GUI。这样即使GUI外观发生变化,也可以保持文件一致性。 美术和视频 功能规范书已经详细列出了美术和视频内容,技术规格书的作用则是解释这些美术和视频内容如何在游戏中进行存储、加载、处理和播放。其中包括动画系统(2D或3D),视频解 压和串流系统。当然有些内容可以采用现成的解决方案,尤其是视频代码。但这里应该提到所有接口技术的问题。 图像引擎:无论你使用精灵、立体像素或3D多边形渲染还是两者兼用,都要在此分别进行说明。虽然只是两句话的描述,但它却可能是这份文件的重要组成部分。要描述视察窗口 、剪辑、特效以及游戏机制中所描述的碰撞和移动函数的关系。  game document(from trac.wildfiregames.com)

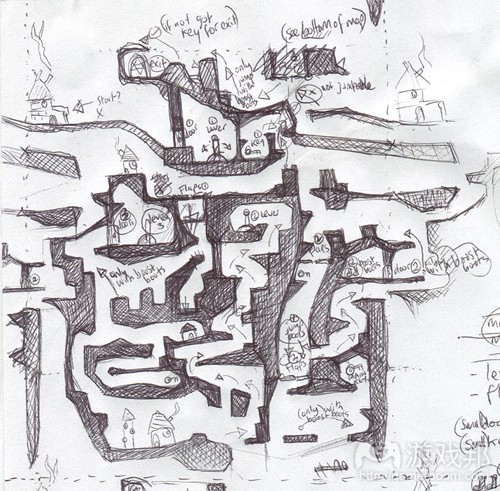

美工说明:要为美工指出其中的重要细节,例如解决方案、色彩深度、调色板、文件格式、压缩、配置文件定义以及美工所需要注意的任何数据。要考虑应创造哪种工具来优化美 术通道,并在此指出其特定说明,或针对更复杂及用户密集型工具创建单独的说明文件。 声音及音乐 在此要描述音乐加载及播放方式。要详细说明混频、DMA、多频道、3D音效等情况。如果用到了第三方驱动器,就要描述它们的界面和用途。要确保能够解决功能规范书所提到的一 切相关需求。 音频编程说明:要为音频工程师及作曲人指出重要细节,例如采样频率、多频道使用、3D音效定义、样本长度等。如果使用到MIDI,要指出其使用版本、数量、可以使用及保存的 乐器类型。要注明数据路径,以及包含特定配置文件的文件需求。要考虑到创建何种工具来优化音频通道,并指出它们的规格,针对更复杂或用户密集型工具创建独立说明文件。 关卡特定码 根据功能规范书中的关卡设计基础,描述如何执行关卡特定码,以及它如何达到预期效果。同时也要描述如果出现更多需求时,其他关卡特定码如何与游戏代码对接。一般来说, 你应该让关卡特定码具有通用性和灵活性,使其方便快捷地运用于其他关卡或新创意的相似需求。 普遍误区 以下是你需要警惕的一些常见错误: *遗漏详情:不可只是列出功能而没有补充如何执行功能的所有详情。撰写这份文件的用意是让程序员事先把开发流程过滤一遍,否则他们无法正确预估执行任务所需时间。 *尽管让各个任务指定程序员完成相应文件内容是一种很有效率的方法,但这并不意味着它能给游戏项目带来最大好处,或者程序员就会在没有监督的情况下自觉完成撰写文件的任 务。在这一过程中初级程序员可能需要一些指导,而在所有文件整合在一起时,所有相关程序员都应该对文件内容进行一番讨论和点评。一些公司设置了让程序员相互评论对方工 作的常规代码复查制度,最好在设计阶段尽早展开这种审核工作。 纸质关卡设计原则 在使用编辑器创建关卡之前,设计师应首先制作纸质关卡设计版本。理想情况下,设计师在项目动工之前就已熟悉设计画板、关卡编辑器和游戏引擎功能。要在执行阶段就根据功 能规范书中的关卡设计核心制作好纸质关卡。 这些核心是关卡或基本需求(会指明需要引进哪些新资产或者设计的限制条件)的核心理念。最好不要一次性做齐所有的纸质关卡设计,因为设计师挨个落实每个新关卡时可以学 到更多。 而制作人通常都希望马车跑在马前面,所以在真正的关卡设计开始之前,要首先制作具有可玩性的原型关卡。这通常是确保工具和游戏引擎顺利运行以制作关卡的一个基础。它也 可以作为编辑器和引擎可实现目标的指南,以及关卡设计愿景的缩影。 紧接着就可以开展真正的关卡设计,但即使到了这一步,说明文件在节省时间和确保产品质量方面仍会发挥重要作用。以下是关卡设计需遵从的重要步骤: 步骤1:小样和讨论 关卡设计师要设想一个符何功能规范书和内容揭露安排要求的关卡布局。然后他们就可以制作一个草图并与主设计师进行讨论。这个小样可以是画在白板上或笔记本上,它是促进 讨论的视觉辅助工具。这里不需要表达整个关卡设计理念或所有关卡细节,因为这些通常是讨论过程中所涉及的内容。  sketched-level(from petermcclory.com)

制作草图和进行讨论的好处在于节省时间,无需迫使设计师事先规划好一切并将其编入文件中。高级或主设计师可以在数分钟内决定大家所提出的关卡设计是否可行,并提出富有 价值的改进建议。一份内容详尽的纸质文件可能需要数天甚至一周时间才能完成。设计师的稿件是否会被退回重新修改,则要视其技能水平而定。这在项目动工初期表现尤为明显 ,因为此时设计师仍在揣摩主设计师想要的效果是什么,临近项目尾声时,要得到原创而富有吸引力的关卡设计就更困难了。 步骤2:详尽的纸质版本 在小样和关卡理念获得批准后,关卡设计师就可以开始制作详细的纸质关卡设计版本了。关卡布局应比草图更详细,并且要按比例绘制出来。最好使用彩色铅笔在大张方格纸中绘 图,在地图中要标注对象、行为、建筑、敌人、事件、位置等信息,也可以将其列入另一份单独的索引文件中。还要列出任务特定美术或代码内容。完成这些细节可能需要花费数 天甚至长达一周时间,但比起在真正的编辑器中“搜索”或“重新设计”,这种方法可以省下更多时间。 完成这一步后,主设计师、制作人和其他主要决策制定者就要对其进行一番审核。他们可能批准这一理念,也可能提出一些修改意见,或是直接否决了这个关卡设计。 另外也要让技术型人员,最好是高级程序员从编程角度审核这份书面关卡设计。这样程序员就会留意关卡设计师的理念所涉及的工具和图像引擎。他们可能向工具添加一些功能, 或者对代码进行调整以让关卡设计更具可行性或更易于执行。他们也可能要求移除或修改任何可能破坏游戏或几乎不可行的关卡设计。 人们通常倾向于跳过这个步骤,直接使用编辑器制作关卡,因为创建一个关卡原型往往比制作纸质版本更快。在项目进度安排较为紧凑的时候尤其如此。但项目安排越是紧凑,就 越有必要使用书面文件来规范设计工作,因为事先考虑周全有助于一次性把事情做完,减少意外情况发生次数,节省返功时间。制作纸上关卡设计版本的好处在于,它可能让设计 师事先就考虑到所有事项,在落实设计之前就表达出关卡的趣味和挑战性所在。这份文件还可以确保在设计师开始工作之前,程序员、美工和音频技术人员就已掌握自己的任务安 排。 步骤3:创造关卡核心 设计师需确定关卡核心游戏玩法,应该在纸上设计版本中就体现其想象的趣味性和挑战性。然后征求主设计师和制作人的反馈意见,让他们决定这个设计的好坏。最终的关卡设计 可能未必有纸上设计版本那样可行,或者有预期那样好玩。但这一做法却有助于节省设计师时间,以免发生重大修改或导致整个关卡都被否决。 步骤4:补充更多细节 确定关卡核心玩法后,要确保其他内容都有助于优化和提升核心玩法。这包括确立设置、充实关卡,使游戏更富生气(例如提供更多选项、解决方案或惊喜)的所有内容。 新美术或代码资产通常看起来都不会很协调,所以要确保设计师在植入占位符前就找到所需内容。然后再更新纸上设计和任务列表。 步骤5:玩法测试 让设计师体验这些关卡,并尽量收集更多反馈。这一过程仍然离不开设计文件。要确保设计师至少要用笔记本记录下所有漏洞,反馈和任务。有时候人们很容易遗漏一些问题,所 以最好是将其归档到含关卡特定问题和反馈内容的数据库中。 文件阶段和开发安排 以下是关于项目进度安排中的典型阶段列表,在每个阶段(或称标志性事件)都有一个评审过程。因为只有当文件大部分内容都完成才能制定项目开发安排,所以要确保重新撰写 文件或创建大家都认同的说明书这一过程不会影响到项目开发时间。为了赶时间发售游戏而匆匆编撰设计文件,并草率投入制作是造成项目失败的一大原因。并且这并不能为你节 省什么时间,事实上它只会浪费大家的精力,并且造成更重大的项目延期。 概念阶段: *文件:游戏理念 *文件:游戏提案 设计阶段: *文件:功能规范书 *文件:技术规格书 *文件:工具说明文件(视情况而定) 制作阶段(游戏邦注:有时也称执行阶段): *制作安排 *技术和美术样本 *首个可玩关卡 *文件:纸上关卡设计(不一定是可交付成果) *Alpha 测试阶段(QA): *Beta——发布首个潜在码 *Gold Master——发布代码 我们还可以列出更多阶段,因为发行商有必要掌握一些决定和确保项目执行顺利进行的途径。有时候它们会针对特定美术、代码和设计制定每月固定标志性事件。这里所列举的只 是一些最为常见并且更有影响力的情况。 应对变化 看到一个项目依从这些原则而顺利运转应该是一件美妙之事,但有时由于灵感或市场趋势的变化也会让项目愿景转向。人们习惯使用“即时设计”模式以应对新变化,并且不影响 项目安排。有时候这种情况确实难以避免,但这种模式也存在弊端。在这种情况下,唯一可用的方法就是固守这些原则及其程序。如果在合同上提到这一点那就更好了。不要在未 更新有关文件的情况下调整项目内容。要知道功能规范书中的一个变化,可能就会导致技术规格书中的有关内容失效,并影响后续的项目安排。主设计师在签收并交付功能规范书 时必须清楚哪些人可能提出修改要求。如果他们确实需要进行一些更改,那就可以通过更新文件和重新制定项目安排而减少其影响。只要想想卡在项目开发过程中,或被迫延迟任 务的痛苦,就足以成为促使你事先考虑周全,制作好这些文件的动力了。希望本系列文件对你的项目开发过程有所帮助。 拓展阅读:篇目1,篇目2,篇目3(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao) The Anatomy of a Design Document, Part 1: Documentation Guidelines for the Game Concept and Proposal by Tim Ryan October 19, 1999 The purpose of design documentation is to express the vision for the game, describe the contents, and present a plan for implementation. A design document is a bible from which the producer preaches the goal, through which the designers champion their ideas, and from which the artists and programmers get their instructions and express their expertise. Unfortunately, design documents are sometimes ignored or fall short of their purpose, failing the producers, designers, artists, or programmers in one way or another. This article will help you make sure that your design document meets the needs of the project and the team. It presents guidelines for creating the various parts of a design document. These guidelines will also serve to instill procedures in your development project for ensuring the timely completion of a quality game. The intended audience is persons charged with writing or reviewing design documentation who are not new to game development but may be writing documents for the first time or are looking to improve them. Design documents come in stages that follow the steps in the development process. In this first of a two-part series of articles, I’ll describe the purpose of documentation and the benefits of guidelines and provide documentation guidelines for the first two steps in the process – writing a concept document and submitting a game proposal. In the next part, I’ll provide guidelines for the functional specification, technical specification and level designs. The Purpose of Documentation In broad terms, the purpose of documentation is to communicate the vision in sufficient detail to implement it. It removes the awkwardness of programmers, designers and artists coming to the producers and designers and asking what they should be doing. It keeps them from programming or animating in a box, with no knowledge of how or if their work is applicable or integrates with the work of others. Thus it reduces wasted efforts and confusion. Documentation means different things to different members of the team. To a producer, it’s a bible from which he should preach. If the producer doesn’t bless the design documents or make his team read them, then they are next to worthless. To a designer they are a way of fleshing out the producer’s vision and providing specific details on how the game will function. The lead designer is the principle author of all the documentation with the exception of the technical specification, which is written by the senior programmer or technical director. To a programmer and artist, they are instructions for implementation; yet also a way to express their expertise in formalizing the design and list of art and coding tasks. Design documentation should be a team effort, because almost everyone on the team plays games and can make great contributions to the design. Documentation does not remove the need for design meetings or electronic discussions. Getting people into a room or similarly getting everyone’s opinion on an idea or a plan before it’s fully documented is often a faster way of reaching a consensus on what’s right for the game. Design documents merely express the consensus, flesh out the ideas, and eliminate the vagueness. They themselves are discussion pieces. Though they strive to cement ideas and plans, they

are not carved in stone. By commenting on them and editing them, people can exchange ideas more clearly. The Benefits of Guidelines Adhering to specific guidelines will strongly benefit all of your projects. They eliminate the hype, increase clarity, ensure that certain procedures are followed, and make it easier to draft schedules and test plans. Elimination of hype. Guidelines eliminate hype by forcing the designers to define the substantial elements of the game and scale back their ethereal, far- reaching pipe dreams to something doable. Clarity and certainty. Guidelines promote clarity and certainty in the design process. They create uniformity, making documents easier to read. They also make documents easier to write, as the writers know what’s expected of them. Guidelines ensure that certain processes or procedures are followed in the development of the documentation – processes such as market research, a technical evaluation, and a deep and thorough exploration and dissemination of the vision. Ease of drafting schedules and test plans. Design documents that follow specific guidelines are easy to translate to tasks on a schedule. The document lists the art and sound requirements for the artists and composers. It breaks up the story into distinct levels for the level designers and lists game objects that require data entry and scripting. It identifies the distinct program areas and procedures for the programmers. Lastly, it identifies game elements, features, and functions that the quality assurance team should add to its test plan. Varying from the guidelines. The uniqueness of your project may dictate that you abandon certain guidelines and strictly adhere to others. A porting project is often a no-brainer and may not require any documentation beyond a technical specification if no changes to the design are involved. Sequels (such as Wing Commander II, III, and so on) and other known designs (such as Monopoly or poker) may not require a thorough explanation of the game mechanics, but may instead refer the readers to the existing games or design documents. Only the specifics of the particular mplementation need to be documented. Guidelines for the Game Concept A game-concept document expresses the core idea of the game. It’s a one- to two-page document that’s necessarily brief and simple in order to encourage a flow of ideas. The target audience for the game concept is all those to whom you want to describe your game, but particularly those responsible for advancing the idea to the next step: a formal game proposal. Typically, all concepts are presented to the director of product development (or executive producer) before they get outside of the product development department. The director will determine whether or not the idea has merit and will either toss it or dedicate some resources to developing the game proposal. The director might like the concept but still request some changes. He or she may toss the concept around among the design staff and producers or open it up to the whole department or company. The concept can become considerably more compelling with the imagination and exuberance of a wide group of talented people. A game concept should include the following features: Introduction Background (optional) Description Key features Genre Platform(s) Concept art (optional) Introduction: The introduction to your game concept contains what are probably the most important words in the document – these words will sell the document to the reader. In one sentence, try to describe the game in an excited manner. Include the title, genre, direction, setting, edge, platform, and any other meaningful bits of information that cannot wait until the next sentence. The edge is what’s going to set this game apart from the other games in the genre.

For example: “Man or Machine is a first-person shooter for the PC that uses the proven Quake II engine to thrust players into the role of an android space marine caught up in the epic saga of the interstellar techno-wars of the thirty-seventh century.” Breaking the introduction up into several sentences for the sake of clarity is acceptable. Just know that the longer your introduction, the more diluted your vision will seem. Background (optional): The background section of your game concept simply expands upon other products, projects, licenses, or other properties that may be mentioned in the introduction; so it’s optional. The background section is physically separated from the introduction so that readers can skip it if they already have the information presented. But the background section is important for licensed properties and sequels and concepts with strong influences from previously released titles in the same genre. If you intend to use an existing set of code or tools or to license a game engine, then describe these items and their success stories here. Description: In a few paragraphs or a page, describe the game to the readers as if they are the players. Use the second-person perspective — “you.” Try to make this section an exciting narrative of the player’s experience. Encompass all the key elements that define the core game play by describing exactly what the player does and sees. Avoid specifics such as mouse-clicks and keystrokes, but don’t be too vague. You want the readers to become the player’s character. Hover your detail level right above the GUI interaction. You would say something such as, “You scan your tactical radar and pick up two more bogies coming up the rear,” instead of “You click on your tactical radar button and the window pops up revealing two bogies coming up the rear.” The description section should make the content and entertainment value of the game obvious and convincing. Key features: Your game concept’s key features section is a bullet point list of items that will set this game apart from others and provide goals to which the subsequent documentation and implementation should aspire. It’s a summary of the features alluded to in the description. These bullet points are what would appear on the back of the game box or on a sell sheet, but include some supporting details. For example: “Advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI): Man or Machine will recreate and advance the challenging and realistic AI that made Half-Life game of the year.” Determining how many features to list is a delicate balancing act. Listing only one or two key features is a bad idea if you’re doing anything more complex than a puzzle game; listing more than a page of features implies that the project would be a Herculean task and may scare off the bean counters. Listing too few features might sell your concept short; listing too many waters down the concepts’ strongest features. Keep in mind that you need not list features that are given, such as “great graphics” and “compelling music,” unless you really think such features are going to be far superior to those of the competition. Great graphics, compelling music, and the like are the understood goals of every game project. On the other hand, if the particular flavor of graphics and music provides your game with an edge in the market, then you should spell that out. Genre: In a few words, define the game genre and flavor. Use existing games’ classifications from magazines and awards as a guide. For example, you could choose one of the following: sports, real-time strategy, first-person shooter, puzzle, racing simulation, adventure, role-playing game, flight simulation, racing shooter, god simulation, strategy, action-strategy, turn-based strategy, side-scrolling shooter, edutainment, or flight shooter. Then you can refine your game’s niche genre with these or other words for flavor: modern, WWII, alternate reality, post-apocalyptic, futuristic, sci-fi, fantasy, medieval, ancient, space, cyberpunk, and so on. Platform(s): In a few words, list the target platform(s). If you think the game concept is applicable to multiple platforms, you should also indicate which platform is preferred or initial. If you intend multiplayer support on the Internet, indicate that as well. Concept art (optional): A little bit of art helps sell the idea and puts the readers in the right frame of mind. Use art to convey unique or complex ideas. Screen mock-ups go a long way to express your vision. Art for the game concept may be beyond most employees’ capabilities, so requiring it would limit the number of submissions; thus, it is optional. If a concept has merit, the art can come later from a skilled resource. Often art from previous projects or off of the Internet will jazz up a document. Just be careful with any copyrighted material. Common Mistakes Here are some common mistakes that developers make in creating a game concept: The concept is totally off base or inapplicable to the company’s current plans. If you don’t want to waste your time writing up concepts that get tossed, find out what the company in question is looking for and keep an ear to the ground for opportunities with which your idea may be a good fit. In terms of resources, the document asks for the moon. Try to keep your concept within the realm of possibility. Keeping the budgets down by suggesting existing tools or properties to reuse is helpful. Limit your ideas to that which can be accomplished in a timely fashion and with a reasonable budget. Limit experimental technologies to one area. Don’t suggest revolutionary AI as well as a new, state-of-the-art 3D engine. If you are being solicited to produce the game concept, find out what the time frame and budget expectations are first. The document lacks content. Simply saying, “It’s Command & Conquer meets MechWarrior where you order your ‘Mechs in tactical combat,” is insufficient. Your description has to explain the actions that the player will perform and make them seem fun. A good description might read, for example, “You order your ‘Mech to fire at point-blank range on the exposed right torso of the Clan MadCat OmniMech.” This kind of descriptive content will help mitigate misinterpretations of the core game play that you envision. The game isn’t fun. A useful exercise is to break down all of the player verbs (such as shoot, command, run, purchase, build, and look) and envision how player performs each. Then, for each verb, ask yourself if it’s fun. Then ask yourself if the target market would find it fun. Be objective. If the action that the player takes isn’t fun, figure out another action for the player to take that is fun or drop the verb entirely. The game-concept document employs poor language and grammar. Don’t make yourself look like an ass or an idiot. Check your grammar and spelling and avoid four-letter words and sexual innuendo. You don’t know who will ultimately read your document or whom you might offend with some particularly expressive words. Even the macho, politically incorrect, culturally insensitive, slang-using manager with whom you exchange dirty jokes over a beer at lunchtime can get quite sensitive with documented verbiage. The designer gives up. Don’t give up submitting ideas. You never know when one of them will take off. Persistence pays off, believe me. Guidelines for the Game Proposal A game proposal is a formal project proposal used to secure funding and resources for a game development project. As a game proposal takes time (and therefore, money) to do correctly, it should only be developed for promising game concepts. The proposal is an expansion upon the game concept. Writing a proposal may involve gathering feedback and information from other departments, especially the marketing department (if it exists). You may need your marketing department to perform some market research and analysis on the concept. If the game requires licensing, you may need your finance and legal departments to investigate the availability and costs involved in securing the license. The programming staff, typically senior programmers or the technical director, should perform an initial technical evaluation of the concept. They should comment on the technical feasibility of the concept and the programming areas that may require research. They should assess the risks and major tasks in the project and suggest solutions and alternatives. They should give a rough estimate as to the required research and development time and resources. The game proposal should include a revised version of the game concept. Technical, marketing, and finance feedback to the concept document might force you to scale back the concept. It might also suggest modifying or adding features. These changes should not take anyone by surprise, as this is the first time that the concept has been subjected to major criticism and the collaborative process. Giving copies of the feedback and analysis to the director of development

(or whoever asked for the game proposal) before they are folded into the game proposal or effect changes in the concept is a good idea. This process not only provides written confirmation that the concept has been reviewed by certain people or departments, but it arms the director with the knowledge to veto, alter, or otherwise approve any proposed changes. The game proposal includes the following features: Revised game concept (preceding) Market analysis Technical analysis Legal analysis (if applicable) Cost and revenue projections Art Market analysis: The marketing department and/or a market research firm, assuming your company can afford it, should compile this information. If you are compiling this information yourself, you should try to avoid pure guesses on numbers. Look for info on the Internet (www.gamestats.com is a good source) and use existing hits in the same genre as indicators for market performance. Target market: The target market is defined by the genre and the platform, issues that have been already addressed in the concept document. You can qualify this definition by mentioning specific titles that epitomize this market. The most successful of these titles will indicate the viability and size of the market. Also mention the typical age range, gender, and any other key characteristics. If this game involves a licensed property or is a sequel, describe the existing market. Top performers: List the top performers in the market. Express their sales numbers in terms of units, breaking out any notable data-disk numbers and any successful sequels. Include their ship date. You can be vague — Q1 1998 or spring 1998. This research can go way back, so present your data in chronological order. List their platforms if they vary from the platform for the proposed game. However, because the markets change depending on the platform, you should always present some title of the same genre on the target platform, even if it didn’t perform as well as the others. Such data may indicate a sluggishness for that particular genre of games on the platform. For example, turn-based strategy games may have great sales on the PC platform, but have terrible numbers on the Sony PlayStation. This list of top performers should indicate this discrepancy if you’re doing a turn-based strategy game.Feature comparison: Break down the selling features of these top performers. Compare and contrast them to the key features described in the concept document. Try to provide some specifics. For example:

Tactical Combat: In Command & Conquer, Dark Reign, and Myth, you order your units to attack specific targets and move to specific places or ranges for an advantage. Most units have a unique strength and weakness that become apparent during play, thus encouraging you to develop superior tactics. Tanktics has a wider variety of orders to allow you to apply superior tactics, such as capture, ram, and hit-and-run. Unit position and target selection become even more important due to terrain, movement, nd range bonuses; firing arcs; and soft spots in rear- and side-hit locations. All of the units have distinct weaponry, armor, and speed to differentiate their strengths and weaknesses and encourage tactics. Not only do you learn to master these tactics over time, but you can also script these tactics into custom orders. Technical analysis: The technical analysis should be written by a seasoned programmer, preferably the technical director or a lead programmer, and then edited and compiled into the proposal. Reviewers of this proposal will use this technical analysis to help them make their decisions. Be honest; it will save you a lot of grief in the end. Overall, this analysis should make the reviewers optimistic about the game’s chance of succeeding. Experimental features: Identify the features in the design that seem experimental in nature, such as untried or unproven technologies, techniques, perspectives, or other unique ideas. Do not include features that have been proven by existing games, even if they are new to the development team. For example, if the team has never developed a 3D engine, don’t list it as experimental. Rather, list it in one or more of the other categories in the technical analysis section. On the other hand, if your development team is working on a 3D engine using the theoretical system of quads, then this effort should be listed as experimental. Of course, by the time you read this article, quads could be in common use. Include an estimate of the time that it will take to bring the experimental feature to an evaluation state, as well as an overall time estimate for completing the feature. Experimental areas generally need more time in the schedule, so the more experimental features you list, the longer the schedule will be. While some companies shy away from such 18- to 24-month projects, many see these experiments as worthwhile investments in creating leading-edge titles. So tell it like it is, but don’t forget to tell them what they will get out of it. Make them feel comfortable that the experiments will work out well. Major development tasks: In a paragraph or a few bullet points, make clear the major development tasks. Use language that non-technical people can understand. Major means months of development. Give a time estimate that assumes that you have all of the resources that you’ll need to accomplish the task. You could also give an estimate of the resources that you’ll need. For example:“Artificial Intelligence Script Parser: Three t four months with two programmers. The parser reads and compiles the AI scripts into lower-level logic and instructions that are executed at run-time.” Risks: List any technical risks. If you don’t foresee any technical risks, by all means say so. Risks are any aspect of research and development that will cause a major set back (weeks or months) if they fail. List technologies that, though they’ve been proven to work by competitors, your company has never developed or with which your company has little experience. List, for example, real-time strategy if your team has never developed a real-time strategy game before; or 3D rendering if this is your first foray into 3D. List any of the major development tasks mentioned previously if you perceive any risk. All untried off-the-shelf solutions (3D engines, editors, code libraries and APIs, drivers, and so on) should be listed as risks because they may end up not fulfilling your particular needs. Any development done by an outside contractor should also be listed, as that’s always a big risk. When assessing risks, you should also indicate the likely impact that fixing or replacing the technology will have on the schedule. Indicate the time in weeks or months that the ship date will slip. List the time impact on specific resources. List any new resources (people, software, hardware, and so on) that would be required to fix it. This section may seem pessimistic, but it creates a comfort level for your document’s reviewers – they will come away with the impression that the game implementation is under control, especially if they can perceive these risks themselves. Plus you’ll have the opportunity to say, “You can’t say I didn’t

warn you.” Alternatives (if any): Alternatives are suggestions for working around some of these experimental or risky features and major development tasks. By presenting alternatives, you give the reviewers options and let them make the choices. List anything that might cost more money or time than desired but might have better results, or vice versa (it may cost less money and time but it may have less desirable results). Whatever you do, be sure to spell out the pros and cons. Estimated resources: List the estimated resources: employees, contractors, software, hardware, and so on. Use generic, industry-standard titles for people outside of the company: for instance, the publisher or investor who might read your document. List their time estimates in work months or weeks. Ignore actual costs (dollars), as that comes later. Estimated Schedule: The schedule is an overall duration of the development cycle followed by milestone estimates, starting with the earliest possible start date, then alpha, beta, and gold master. Guidelines for the Game Proposal, continued Legal analysis (if applicable): If this game involves copyrights, trademarks, licensing agreements, or other contracts that could incur some fees, litigation costs, acknowledgments, or restrictions, then list them here. Don’t bother mentioning the necessity of copyrighting the game’s title or logo, as these are par for the course and likely to change anyway. Cost and revenue projections: The cost and revenue projections can be done in conjunction with the finance and purchasing departments. This data should give the reader a rough estimate of resource costs based on the technical analysis’s estimated resources. Resource cost: Resource cost is based on the estimated resources within the technical analysis. Employee costs should be based on salaries and overhead, which the finance or payroll department should provide. You can list these as average by title or level. Any hardware or software that you purchase should be listed as well, even if it will ultimately be shared by other projects or folded into the overhead budget. Use a table or embedded spreadsheet as it is easier to read and edit. For example: Additional costs (if any): This section is an assessment of additional costs incurred from licensing, contracting, out-source testing, and so on. Suggested Retail Price (SRP): You should recommend a target retail price before your game goes in the bargain bin – pray that it does not. The price should be based on the price of existing games and an assessment of the overall value being built into the product and the money being spent to develop and manufacture it. Of course, your distributors will likely push for a lower sticker price or work some deals to use your game in a promotion that will cut the price even further, but that will all be ironed out later. Keep in mind that the higher the sticker price, the lower your sales, especially in a competitive genre where there’s not as much demand as supply. Revenue projection: The revenue projection should show pessimistic, expected, and optimistic sales figures using the costs that you’ve already outlined and the suggested retail price. Other factors, such as marketing dollars and company overhead, should be left out of the picture as these are subject to change; if a minimum marketing budget is known, however, then you should certainly factor it in. Often the revenue projection is best represented with a pie chart or

a bar chart. Be sure to indicate with an additional wedge or bar the costs incurred from any of the risks described in the technical evaluation and show totals with and without the risk assessment. Art: If your game concept did not include any art, then the game proposal certainly should. The art should be created by skilled artists. Dispose of or replace any of the art in the concept document that was not created by the artists. The art will set the tone for the game. Assume that the readers may only look at the art to evaluate the proposal, so be sure that it expresses the feel and purpose of the game. Include a number of character, unit, building, and weapon sketches, in both color and black and white. Action shots are great. Include a GUI mock-up if your game is a cockpit simulation. Be sure to have good cover art. Paste some of the art into the pages of the documents, as it helps get your points across and makes the documents look impressive. Presentation: The whole proposal, including the revised concept document, should be printed on sturdy stock and bound in a fancy report binder along with copies of the art. This document is to be presented to business people – you know, those people who walk around your office wearing fine suits to contrast with the t-shirts and cut-offs that you normally wear. Don’t forget that you’re proposing a major investment, so make the proposal look good and dress well

if you’re going to handle the presentation. Preparing a slide show in a program such as Microsoft Persuasion is helpful for pitching your key points and art. Common Mistakes Some common mistakes in preparing a game proposal include: The analysis is based on magic numbers. Try to back up your numbers by listing your sources or explaining how you came up with them. Watching a producer pull some numbers from thin air and throw them in the document is almost laughable. The proposal is boring. This is a selling document. Don’t bore the readers. Give them facts, but make these facts exciting, concise, and convincing. The proposal fails to anticipate common-sense issues and concerns. You should find out what this proposal is up against — other proposals, competitive products, financing concerns, cost and time expectations, game prejudices, and historical mishaps. Your proposal will stand a much better chance of being approved if it addresses these issues preemptively rather than getting besieged by them during the review process. The proposal writer is overly sensitive to criticism. My experience might be unique, but don’t be surprised if the major promoter for your game proposal decides to play devil’s advocate. Make sure your proposal is solid. Believe in it and remain confident, and you’ll weather the criticism and make believers out of those reviewing your proposal. The proposal writer is inflexible to changes to the game. Often during the process of gathering research or receiving criticism from the review committee, some reasonable suggestions will arise for changing or scaling back the design. Game development is a collaborative process. Take the feedback and change the design, or the game could die right there. The key word here, as tattooed on the arm of my buddy who served in the Vietnam War, is transmute. He had to

transmute to stay alive and keep going, and your game idea may have to do the same. This concludes part one of a two-part series on the anatomy of a design document. In the next part, I’ll taunt you with some more colorful metaphors interspersed with some useful guidelines for creating functional and technical specifications and level-design documents. I’ll also give you an overview of the document review process and how it facilitates the game development cycle. Did you ever look at one of those huge design documents that barely fit into a four-inch thick, three-ring binder? You assume that by its page count that it must be good. Well, having read some of those design volumes from cover to cover, I can tell you that size does not matter. They are often so full of ambiguous and vague fluff that it was difficult finding the pertinent information. So why does this happen? Because the authors didn’t follow guidelines. This article is part two of a two part series that provides guidelines that when followed will ensure that your design documents will be pertinent and to the point. Unlike the authors of those prodigious design volumes, I believe in breaking up the design document into the portions appropriate to the various steps in the development process – from concept and proposal to design and implementation. I covered the first two steps in part one of the article, providing guidelines for the game concept and game proposal. This part will provide guidelines for the two heaviest undertakings – the functional specification and technical specification, as well as some guidelines for the paper portion of level design. Functional vs Technical Specifications Traditionally in the game industry, there was only one spec. How technical it was depended on who wrote it. Any documentation the programmers wrote afterwards to really plan how they were going to implement it was informal and often remained on white-boards or notepads. Yet in order to ensure the project would proceed without hazard and on time and on budget, the documentation needed to be more technical. Such detailed technical specifications took time –

time wasted if the goals and function of the product should change or fail to gain approval. This problem was tackled as more and more seasoned programmers and managers of business software development moved into games. They brought with them new standards for documentation that helped ensure more accurate plans and less technical problems. They introduced a division in the design document between goals and method and between function and technique. They separated the design document into the functional specification and technical pecification. This

way, the clients, users or principal designers of the product could review the functional specification and approve the goals and functions of the proposed software – leaving the determination and documentation of the methods and technique up to the technical staff of programmers. Therefore, the technical staff waited until the functional specification was approved and signed-off before starting on the technical specification. They worked from the functional specification alone, ignoring any design changes that occurred after sign-off unless the spec was updated and a new schedule agreed to. Thus the division saved time for the rogrammers and gave them more control of the schedule, while still ensuring they had a complete plan for the methods and technique for implementation. Many companies still refer to the functional specification as the “design document” and yet also produce a technical specification. The term “functional” is a clearer term adapted by businesses and these guidelines to clarify what is expected in the document. Here is a link to a formal definition: http://webopedia.internet.com/Software/functional_specification.html In short, what goes into the game and what it does is documented in the functional specification. This is often written from the perspective of the user. How it is implemented and how it performs the function is documented in the technical specification. This is often written from the system perspective. Both form important deliverable milestones in the design stage of the game development process. Guidelines for the Functional Specification The functional specification (or spec for short) outlines the features and functions of the product. The target audience is the team doing the work and those responsible for approving the game design. The functional spec is a culmination of the ideas, criticisms and discussions to this point. It fleshes out the skeleton of the vision as expressed in the game concept and game proposal. It is a springboard from which the technical specification and schedule is derived and the implementation begins. It’s important that it is all written from the user perspective. In other words, what is seen, experienced or interacted with should be the focus of the document. It’s often very tempting (especially to programmers) to create something that’s very system oriented. This often leads to distraction and hard- to-fathom documents. Readers are really just looking to this document to visualize what’s in the game, not how it works. The length can vary from ten pages to a few hundred, depending on the complexity of the game. You really should not aim for a page count. I’ve seen and written really GOOD design documents that were less than fifty pages and some that were much more. It is just important that each section under these guidelines be addressed. This will eliminate the vagaries and guesswork that comes with insufficient documentation and the apparent need to ramble-on that comes with aiming for a high page count. The time involved in writing the functional spec is anywhere from a few days for say a puzzle game, a month for a shooter, to a few months for a complex game such as an RPG or strategy game. The amount of time spent may not be congruent to the resulting length. The discrepancy comes with deliberation time, especially if the game has any unique, unexplored qualities or if the game play is particularly deep. Of course, how efficient the principal designers are in

making their decisions is of enormous impact as well, especially if everyone is particularly imaginative and passionate about the game. For many, this functional specification is where the documentation begins. They skip the important research and review phase of the concept document and game proposal, which would otherwise help it anchor the vision and target market firmly in place. By skipping the first steps, they also put off the inevitable criticism from marketing, finance and technical staff, which leads to wasted efforts. The game’s lead designer usually produces the functional specification. It may be a compilation of other’s work and hence a cooperative effort or it could simply be a matter of putting the vision of the producer on paper. Sometimes the producer will produce the document him/herself; which is ideal for assuring that the vision expressed is indeed what the producer desires. Like the game of telephone, sometimes the message gets altered when it goes from the lead visionary to the author. Whatever the process and whoever the author, it’s important that the producer and lead designer totally agree with everything expressed in this document. They cannot be preaching one thing and documenting another or the documents will be ignored and serve no purpose. I’ve never seen a design that didn’t undergo some changes during implementation, but the process of communication has to be expressed through the specification, even if it requires updates or an addendum. Some changes need to be fast and furious due to time constraints so the documentation may be light. So, even if it’s an electronic memorandum or notes on a piece of paper, be sure to distribute these and attach them to all future copies of the specification. If the vision of the game changes, however, it’s best to start from the beginning with a new concept document and proposal. The clarity the updated documentation brings will save time in the long run. Unlike the game concept and proposal, the functional specification is not a selling document. It merely breaks down and elaborates on the vision in very clear terms understandable by every reader. It can be a little boring or dry as the necessary details are filled in. I’d recommend putting in summary level paragraphs at the start of every section, so that readers can get the gist without skipping any sections or losing any confidence in the thoroughness of the specification. Why do I recommend this? Well, the question should really be “Why do some people never find the time to thoroughly read the project specifications?” While your company’s managers and team members might not fail in this regard, there’s always a third party, like the publisher or contractor. On the other hand, this document cannot be technically explicit, as its readers are mostly non-programmers. If you find yourself getting technical, stop. That’s what the subsequent technical specification is for. Besides, getting technical with a bunch of non-technical readers can make their eyes glaze over or open up a can-of-worms. You don’t want to give them an invitation to stick their nose into something they don’t necessarily understand and really shouldn’t care about. Likewise, you or the other authors may be non-technical, and you shouldn’t be dictating to the programmers how they accomplish what you want them to do. Let them determine that when they write the technical specification. This document is purely for the communication and approval of what goes into the product as opposed to how to accomplish it. Limit descriptions of how something should be accomplished to those areas that are you believe are really important that it work a certain way. For example, you would not indicate what variables to use and how to use them to simulate a law of physics; however, you might want to indicate the factors involved in the physics equation. Similarly, telling a programmer how to define his data structures and objects is a bad idea, but proposing the interface for data entry and the delineation of data is certainly within the confines of function. The functional specification can be broken down into a few major sections: •Game Mechanics •User Interface •Art and Video •Sound and Music •Story (if applicable) •Level Requirements Game Mechanics The game mechanics describe the game play in detailed terms, starting with the vision of the core game play, followed by the game flow, which traces the player activity in a typical game. The rest is all the infinite details. Core Game Play: In a few paragraphs describe the essence of the game. These few words are the seeds from which the design should grow. Planted in the fertile soil of a known market, they should establish roots that anchor the vision firmly in place and help ensure a successful game. This is similar to the description section in the game concept, except that it’s non-narrative, and usually expressed clearest in bullet points, though this could vary depending on the type of game. Game Flow: Trace the typical flow of game play with a detailed description of player activity, paying close attention to the progression of challenge and entertainment. If the core game play is the root of a tree, the game flow is the trunk and the branches. All activity should actualize and extend from the core game play. Be specific about what the player does, though try to use terms like “shoot”, “command”, “select” and “move” rather than “click”, “press” and “drag”. This keeps the description distinct from how the actual GUI will work, which is likely to change. Refer readers to specific pages in

the User Interface section when you first mention a GUI element such as a screen or window or command bar. Characters / Units (if applicable): These are the actors in the game controlled by the players or the AI. This should include a brief description and any applicable statistics. Statistics should be on a rating scale i.e. A to Z or Low to High, so that it’s clear where units stand in relation to each other in broad terms. It’s a waste of time plugging in the actual numbers until the programmers have written the technical specification and created an environment for you to experiment with the numbers. Special talents or abilities beyond the statistics should be listed and briefly described, but if they are complex, they should be expanded upon in the game play Elements section. Game Play Elements: This is a functional description of all elements that the player (or characters/units) can engage, acquire or otherwise interactive with. These are such things as weapons, buildings, switches, elevators, traps, items, spells, power-ups, and special talents. Write a paragraph at the start of each category describing how these elements are introduced and interacted with. Game Physics and Statistics: Break out how the physics of the game should function, i.e. movement, collision, combat etc., separating each into subsections. Describe the look and feel and how they might vary based on statistics assignable to the characters, units and game play elements. Indicate the statistics required to make them work. Get feedback from the programmers as you write this, as how the game handles the physics and the quantity of the statistics will