|

今天我们要讨论的是一个甚为重要但经常被人忽视的话题。多数电子游戏开发指导和教程都没有承认沟通在游戏开发技能中的地位。 知道如何开口和有效写作与知道如何编程、使用Photoshop、遵守设计流程、创建关卡、作曲或者准备音频一样重要。这些都是某人在准备好将沟通这种技能呈现给团队之前所需要 学习的技术,需要掌握的概念,以及需要完成的练习。  comunication-skill(from utm.my)

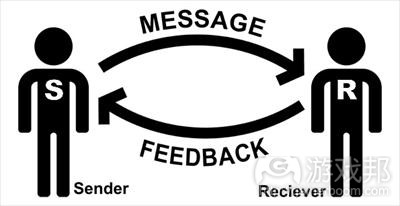

游戏开发者尤其如此 当然,世上人人都需要沟能,并且可以从中获得更多益处。但我们为何专挑游戏开发者来讲? 我并不是说只有游戏开发者才存在沟通问题。但根据过去十年与数百名计算机科学系的学生、独立开发者以及专业软件工程师打交道的经验,我可以说我所遇到的游戏开发者普遍 存在一个特定的沟通问题。这也是我们所面临的一个特殊问题,因为这并不单关系到一天的工作是否顺利,我们的沟通能力还会对我们是否能够合作甚至是独立完成工作产生实实 在在的影响。游戏开发者通常为自己的工作而兴奋,但无论是因为技术局限性还是因为沟通局限性而导致某些很棒的功能无法实现,那都会让游戏遭殃。 分清工作职责 如果程序员负责编程,设计师做设计,美术人员做美工,音频能力制音频,这里会有相同的沟通角色吗? 当然,甚至还有好几个。 制作人。即使是在小型业余爱好者或学生团队中,这通常也会由其他角色所包揽,制作人专注于团队人员之间,以及团队成员与外界的沟通问题。有时候这项工作会被误解为分配 安排,但要制定这种分配计划则需要大量的交流和邮件往来,以及让所有人都处于同一轨道的持续沟通。 设计师。设计师在游戏开发过程中的角色之一就是通过游戏与玩家沟通。指出游戏目标是什么,哪些内容会对玩家受害或者受益,玩家下一步应该去哪里,从而传达游戏的内部状 态信息——这对游戏设计的影响远大于编程。根据游戏团队的技能组合情况,某些情况下设计师与游戏的直接工作就是关卡布局或数值调整,如果大家的工作互有交集,设计师与 程序员、美术人员及其他人员的沟通交流更为重要了。在一个人担任多个角色的小型团队中,沟通就成了让其他人知道游戏状况的一个必要环节。 主管。在一个拥有主管的大型团队中(常见于专业团队),主程序员,主设计师或主美术师还得具有出类拔萃的沟通才能。这些人并不一定需要是最出色的程序员、设计师或美术 师——虽然他们当然需要具有这方面技能,但他们是因为能够有效领导他人而身居高位,而这又涉及所有方向的大量沟通:与上级、下级之间的沟通,甚至协调上下级和他人之间 的沟通。 文案:并非所有游戏题材都需要文案,但对于那些需要写作内容的游戏来说,沟通就显得更为重要了。与那些并不身兼程序员一职的设计师相似的是,除了一些实际对话或其他游 戏内置和插页文本之外,团队中的文案通常并不直接创造多数内容或功能。会写一些东西并不能算是称职的文案,文案和内容创造者还应该同他人频繁交流,以确保执行效果与自 己所想象的世界完美融合。 非开发角色。这一切只考虑到了开发过程中的团队内部交流。学习如何与测试人员、玩家或者项目消费者和潜在新雇员(这里甚至还忽略了投资者和财务专业人员)更好地交流, 则是另外一个巨大的挑战,如果团队规模够大的话,你还得同人机互动专家、营销专家、PR人员以及HR员式沟通。如果你是一名业余爱好者,学生或独立开发者,你就得自己扮演 好这所有的角色。 我们通常遇到的沟通问题有两种。虽然它们看起来好像是两个极端,但实际上这两者之间并没有看上去那样泾渭分明。在特定情况下,其中一者甚至可能从另一者演变而来。  Interpersonal-Communication(from onetechgeek.com)

挑战1:羞怯 首个问题就是我们有些人比较害羞。我所遇到的一些极具天份的程序员、设计师、美术人员和作曲家就是害羞的人。这实际上会限制他们的创作——如果他们无法大声说出自己的 想法,就可能给游戏、团队或者公司造成损失。 不幸的是,我们很容易为害羞找到借口。毕竟,这些有才华而害羞的人之所以能够发展自己的专长,就是因为他们能够远离喧嚣,独善其身地修炼自身本领。但遗憾的是,这种想 法不利于帮助他们和团队从中获益。 团队成员之间的交流在游戏开发过程中的作用不容小觑。有时候你得在3D Studio Max上完成工作,有时候又需要拿出来大家一起讨论才可能完成工作。 我发现害羞的另一个因素在于,人们知道自己所在领域的出色之处,他们总能看到自己的工作要达到自己的预期,还有很大改进空间。 一个人在所在领域的人群中处于什么地位并不重要,重要的是项目中的开发者比其他人更清楚其中的不同之处。由于大家的专长、兴趣和背景各有不同,所以这就难免会成为一个 问题。 挑战2:避免争执 有时候害羞看似由于过去不太成功的互动而形成的过度补偿。有人想开口来分享自己的想法,补充他人的观点,但却遇到了伤害,也没有取得什么成果。参与讨论容易让人们激动 和生怒,所以有名开发者在一次无谓的挣扎之后终于放弃了。也许他们觉得自己的想法并没有得到合理的接受,甚至它根本就不值得自己卷入这种麻烦中。 我的一名大学导师曾经向我指出:“Chris,有时候人们挑战你的观点时,他们并不是真的在否定你的说法。他们只是不认同你的表达方式!如果你用不同的方法说法同样的观点, 可能他们就会支持了。” 他说的完全正确。我听到这种说法后,除了突然让自己住嘴,也开始发现其他人也存在这种情况。会议、合作型课堂项目,甚至是人们的日常交流都会产生冲突,那些心地善良, 无意冒犯他人之人,确实总体上会认同双方的目标和观点,而普通人无意识的敌意升级却经常引起事与愿违的反复争执。 造成这种问题的原因和行为模式有不少。在10年的研究之后,我开始更理解这一点,这种情况仍然时有发生,它仍然是我必须积极应对的情况。 这就不难理解人们在感觉自己融入团队就是麻烦的起源之前究竟遭遇过多少次这种情况。这种情况的结果就是回避,降低自己在对话中的个人投入,并服从人们在讨论中所达成的 一些行动项目。 如果沟通技巧很糟糕,无论其他技术或美术技能再好,你都很难得到他人的帮助,很难得到玩家和评论人员的关注。另一方面,如果你的沟通技能十分了得——极具说服力、清晰 、公正而富有条理,那么你能够处理的项目范围和类型可能就会惊人地扩展,因为作为优秀的沟通者最关键的地方就在于,成为任何各具才能(以及经验、灵感)的开发者所组成 团队中极有意义的一部分。  communication(from practicalpmo)

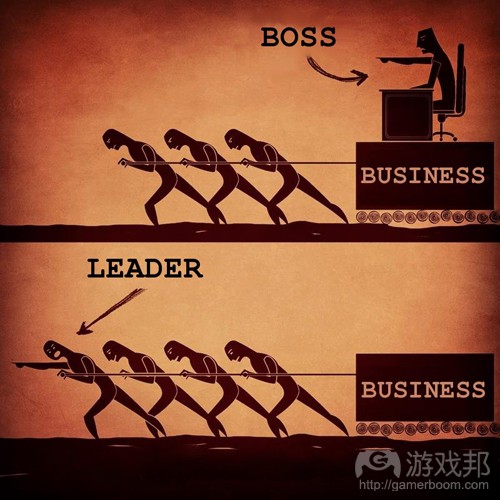

用心聆听 仔细倾听,意味着不但要听到他们在说什么,或者给予他们一个发泄口,还要试着与他们共同理解潜在意思,而据此作出相应的调整则远比听起来更困难,或者至少是比我们所想 的更不自然。你可以通过训练自己更好地倾听而受益。我之所以能够这么说,是因为任何人(无论是总统和实习生,家长和孩子,学生和老师)都能够更好地倾听。 但这里有个倾向就是,将自己视为主角,其他人则是NPC,尽管我们理智地知道这种做法是不现实的。倾听的部分要素在于有意识地依此行事。其目标并不是让他人来适应你的想法 ,而是通过大量背景和视角,以让人们获得参与其中的良好感受而找到前进的出路。 不要在乎谁赢 对话沟通中并不存在谁是赢家的问题。 这个道理听起来显而易见,但有许多人仍然没有充分理解。开发讨论并不一定是场争论。即使是创意冲突也不可避免地会呈现某些不可兼容的想法都在争夺日程表上有限的开发关 注点的局面,但争论并非解决问题的良方。 在一个交流对话的模式中,两个持有不同观点的人参与其中,最后其中一者赢了,另一人却输了。我并不认为任何人都会有意识地认同这种对话模式,但从我们在电话上所看到的 政治人物谈话的头部特写,电影角色之间的对话,甚至是我们本能的斗争或逃跑意识都会将此视为一种默认的对话模式。 不要去想谁是观众(注:要尽量避开其他观众,因为这通常可能以防御性、自我保护的姿态污染一个文明的对话环境),或者想象公正的裁判会判断谁是赢家,要考虑参与其中的 人所处的立场可能会影响到将来的争论。 如果你所有的先决参考材料都在引导你强烈地相信某一特定方向,你可能只是在推波助澜地给这个夸张的方向帮倒忙了。无论何时我们遇到一个不太喜欢,尤其是涉及设计、美术 或商务等可能有许多可行方向的领域,只要我们将其与消极、敌意的人联系在一起,那无论是哪种理论依据在支持这项选择都没用了。 要友善地对待此事。首先要担心的是理解他们观点的优势和考虑,然后才是你自己的观点得到理解和考虑。注意这两者都不是要“说服”他们,或者向他们展示“正确的”方法, 而是尝试相互理解,因为如果没有这个前提,其他的讨论内容都只会沦为针对不同想法的争吵。 可能是你错了 谈到相互理解:不要害怕在想出发生什么情况后放弃一个观点,并意识到还有另一个更可行的方法。我们总是顾及面子问题而坚持捍卫自己的观点——尤其是在还没有吃透这些想 法的情况下。 聪明人在遇到新信息或顾及新的考虑时总是善于变通。你们并不是在玩红队对抗蓝队的游戏。你们是同一个团队中的人,要尽量向同一个方向传球,也许你的队友更清楚哪个方向 才是正确的目标。 另一方面就是要给其他人摆脱困境的出路。提供一些新信息或关注点,让他们更容易改变自己的想法,即使这些信息实际上并不足以改变他们的想法(因为这可以让他们用更合适 的方式 回应新信息,而不是一开始就表现出不确定性)。承认他人所在立场的优势并不会让你的立场处于弱势,这只不过是让他们觉得自己的想法被倾听和得到了认可,以及你考 虑的并不只是自己的初始想法,还包括他们的想法。无论是以哪种方法解决一个问题,都要允许大家存在不同的见解,而不是形成谁站在你一边,谁反对你的印象(实际上,通情 达理的人一般是反对特定观点而不是针对某人)。 当某一观点不可避免地被妥协或放弃时,作为富有技巧的沟通者就不要对此太刻薄或者穷追不舍了。不要介入太人私人感觉,这是团队的最高利益,并非每个建议都可能被采纳或 者最终被游戏所保留。 假定无过失,就要假设是最好的情况 所谓的稻草人论证就是指我们不赞同或者试图反驳一个简单化的反对立场这种情况。在非正式情况下,针对政治分歧或者宗教/文化信仰的激烈争论,经常可以见到人们反对团体中 最为极端、非理性或明显棘手的成员,而不是去对付那些更中肯、理性和富有说服力的信徒。这就会陷入一个僵局,由于双方都觉得自己在推进一个反对对方的观点,所以任何一 方都不会觉得自己的问题得到了解决。 如果大家的目标是形成一个更为成功的合作,而不只是让自己暂时感觉良好,那么最正确的做法就是采用与稻草人论证相异的做法。假设他人是出于理性、正式和好意的立场,如 果这并非你在沟通中所看到的现象,那就去进一步理解对方。或者甚至可以帮助他们进一步发展他们的想法,寻找对方所没有想到的其他优点——也许从这一点出发可以让那些原 本与你无关的立场受益。 如果你所持有的观点与他人的提议并不相同,最好将自己的想法提出来,同时再提出另一个可以作为替代性方案的想法。如果它被另一个你通过真正的讨论和考虑所提出来的更好 的建议所取代,或者形成了一个似乎对双方都有好处的想法,那就更好了。 你的挫折感会形影不离 这是我通过自己的摔跤训练生涯而得到的一点生活经验。多数时候当人们不安或受挫或者失望时,他们多半是对自己失意和失望,而通过责备将矛头指向他人却并不能疏散这种情 绪。 即使这在任何情况下并非100%正确(当然,有时候人们可能会非常欠考虑,自私或者不负责任,你有理由对他们感到失望)——我发现假想我们自己的情绪状态是一个非常管用的 方法,因为它让外界的事物得到了控制和变化,以便我们专注于自己所能做的事情。 对有违我们信任的人感到失望?我们的失望可能是源自我们无法认识到我们不应该信任他们。对做错事的人生气?我们可能是气自己没有把握好方向或者期望太高了。对不理解那 些你认为显而易见的事情的人感到抓狂?你可能是因为觉得自己无法向他们清晰而高效地描述事件而受挫。 如果人们没有很好地理解或接受你的观点,但你却相信自己的想法具有价值,只是没有得到充分的考虑,不要将此归咎于他人的理解无能,而要想想这是因为自己没有表达清楚。 也许他们不会遵从你的参考意义,或者无法更好地通过简单的图表或流程图而理解你的想法。也许他们理解了你在说什么,但却不知道为何你会认为这值得一提,或者他们知道你 的意思但就是不懂你所想的事情与你所认为的改变之间有何联系。 最好是写下概括性的重要内容(游戏邦注:人们通常难以吸收含有大量细节的论据,除非他们已经知道其中的大意),并以其他方法来解释说明。提供一个展示案例。如果你已经 有一个自己认为很重要但却没有得到认可的观察,最好是以另一种新方法引出这个观点,而不是令其夹杂在其他混乱无章的字词中,导致其无法合理地呈现或得到支持。 将假设性误会为决定性 结论可能会变。当他们处于初稿阶段时,他们很可能会这样——这正是我们为何要制作初稿的原因!因为它们还只是一个计划、理念或一个原型时更易于修改和调整,它们越是成 型其结论就越为牢固。 这种误解会产生两种错误的沟通方式:将你自己的假设性理念误理为决定性的,或者将他人的假设性理念误解为决定性的。在开发阶段,随着更多人的参与,项目就会发生变化从 而反映出哪些做法可行或不可行,或者更好地利用团队成员的强项或兴趣。 如果你早期在项目中推进了一个人们看似赞同的想法,但之后则可能因开发过程中发现由于时间和资源有限,而不得不对其改进或删减。它甚至可能被完全删除,甚至在混乱中完 全被忽略了。在提到它的案子之前,要先重新考虑一下项目可能会如何变化(因为当时该想法只是刚刚成形),以便决定是否需要更新这一想法,令其符合团队和游戏发展方向。 有时候某些想法在开发过程中的价值就是给予我们专注的方向,而该理念能否保持其原来的形式则要让位于团队和玩家是否会喜欢游戏。它可能需要重新加工,可能需要进行一点 调整,也可能在最后的开发阶段却发现它并不像现在这么可行了。也有可能你最终还是得放弃它,尽管它曾经是团队过去所实现理念的垫脚石。 另一个做法就是犯同样的错误,从而了解他人的想法:在它们还是假设性的时候将其想象成决定性的。这种情况的发生也许要归因于该想法距离未来结果还很远,以及初始理念和 讨论发生时大家还没发现或解决的问题。如果一个目需要人们有意支持一打汽车类型,但在开发过程中实际上只用了三种不同的汽车 ,以便将精力运用于其他必须的开发环节, 那就会发生这种情况。人们会变得乐观,人们会犯计划性的错误,人们无法预测未来——但重要的是不要将这些人类瑕疵与有意的谎言或不守信混为一谈。如果有人在开发早期说 出了一个项目之后可能实现的愿景,不要太当真,也不要将其视为板上钉钉的合约,只要将其视为他们所打算的方向即可。执行的过程中实际上还需要妥协。 软化确定性 团队内斗的一个普遍起源就是对某一个观察或说法的确定性的错位感,它反映了团队其他人并不一定认同的价值优先权,尤其是当有一个人的说法凌驾于团队其他人优先权之上的 时候。 最好是谦逊地承认自己只能看到部分情况,你所能做的就是从自己的立场出发澄清事情的发展方向。为大家的争议留有余地,“我最多只能说……”或“在我看来……”或“我当 然不可能代表所有人,但至少根据我所玩过的该类游戏题材来讲……”这类开场白看似无甚作用,但实际上却可以避免将团队拴死在一个结点上,从而根据不同角度展开有意义的 讨论。 顾问的挫折 校园里充斥着大量想法与行事风格一致的人,他们拥有相似的价值观,通常也是同一代人。在教室之外,无论是合作开发一个游戏项目,加入一家公司,或者做其他事情,似乎都 是这种情况。通常情况下,如果你的技能是视觉艺术,寻径你就得同那些不是很懂视觉艺术的人合作。如果你的技能是设计,你就得与许多非设计师共事。如果你具有技术专长, 你就得同大量非技术人员打交道。 这也正是你在团队中的原因。因为你知道他们所不懂的内容。你可以看到他们所无法看到的问题。你知道他们不知如何应对的方法。如果团队或公司中的其他人能够以相同的方式 理解你的想法,寻径他们可能根本就不需要你参与了。你在这个位置的目标就是帮助他们理解问题,而不是因为他们的理解与你不同而看轻他们。要帮助他们看到你所见到的内容 。 我将此称为顾问的挫折,因为它特别强调一点:如果有一家并不了解销售(或者设计、IT等领域)的公司给一名销售顾问打电话,就是因为他们不了解这个领域所以才会打电话咨 询。此时幼稚、缺乏经验、没有准备的顾问对此情况的一个可怕反映就是——这些人怎么会对如此基础的内容一无所知?顾问的作用是找到这个认知差距,并给他们补上一课,而 不是因此而贬低他们。毕竟这家公司还要做大量专家所不能完全理解的事情,因为这些并非他们所熟悉的领域。 如果你发现了一些与自己有关的问题,要与团队分享。因为这正是你存在的部分价值。你也许会看到团队中其他人所不能见到的方面。 每个角色的价值不同 上述要点的另一面就是欣赏其他不如你自身观点更显而易见的因素和问题需要同这一点相平衡,在某些情况下甚至需要颠覆它。 挫折可能起源于顾问挫折的一种夸张形式:程序员可能会本能地将团队中的其他角色视为二级程序员,设计师可能将其他人视为二级设计师等等。这并不是一种有效的思考方式, 因为他们不适合你的位置,而且你也不并适合去做他们的事情。位置不局限于某人推动项目进程的技能,它还代表他们在团队中对项目的某一方面所持有的一种责任和身份,一种 看待特定问题的专业眼光。程序员可能无需担心色彩方案,美术人员可能不用操心如何编程,而只要玩法可行,设计师也不需要顾虑美术和编码问题。 这正是让人们各司其职的好处之一,即便团队是由身兼数职或者独立开发项目的成员组成。 由于大家的出发点不同,开发过程中就难免出现妥协。美术人员可能会因图像渲染的异常问题而烦恼,但工程师可能会有团队已经使用了他们可用的技术来支持这种美术风格但却 仍然无法实现的正当理由。音乐或音频设计师可能会觉得某些增进谱或动态调整方法可能会让游戏的音频增色,但玩法或关卡设计师则可能有一些自己所熟悉的关于用户体验、站 程或输入方法等棘手问题。 制作人有时候口碑很差的原因之一就是,作为项目“经理”他们并不理解这些情况,因为他们的职责是确保游戏取得进展,直到按时完成和发布为止。所以他们遇到这些问题的妥 协理由通常就是,“……但我们得按计划完成游戏”。如果某人不为此而努力,那么项目就无法完工。 所以当你有幸与一支优秀而平衡的团队共事时,要善待团队中的其他人,因为他们都在找你所看不到的盲点。要让你自己成为一名更出色的沟通者,这样你才能为他们提供同样的 帮助。 过于强调角色作用 现在我觉得有必要特别说明一下小型团队开发角色在讨论和考虑过程中不应该卷入成员的能力分类问题。 虽然绘制视觉艺术的成员很可能是美术风格的最终决定者(游戏邦注:这不仅是一个美学偏好问题,还是一个他们在工作中因自身的能力、强项与局限性所带来的副作用),但这 并不意味着团队中的其他人就无权提供一些自己对该美术风格的反馈和建议(要知道,美术人员可能只能创造一种特定的视觉风格,但这并不意味着程序员就应该全力以赴实时支 持这种风格),应该允许他们提出自己的意见,并以游戏粉丝或媒体的身份来谈谈看法。 一名团队成员真的比项目中的其他人更了解动画吗?果真如此,那么这名成员就应该参与同动画执行或部署相关的讨论。但即便你不是动画人员,如果你能提出大量不同的媒体案 例,并且有一个如何令之与技术、设计或其他学科相互作用的执行想法,那么你还是有必要参与讨论(尽管其决定权仍在于最有影响力,以及最有相关经验的那个人)。 躲藏在自己的角色背后,认为“我并不是美术人员,所以这不关我的事”或者“我是设计师,所以这不是你需要担心的问题”并不会给团队带来好处。游戏质量会影响到每个参与 其中的人。你可以提出一个与自身有关的看法,并由拥有不同背景和不同观点的人来提出意见。大家一起找到最佳方法。  boss-leader(from hobbygamedev)

与这些角色说明相关的一个区别理念就是仆人型领导。它提倡的是团队领导不应该像制作人、总监或主设计师一样将自己视为其他人的上司,他人只能服从自己的命令,而要像团 队中的另一名合作者一样与大家共处,所不同的只是自己还负有监管项目方向以及抽取不同经验类型的责任。他们必须平衡自己与他人的想法,从而让大家形成一个共识,要尽量 让团队保持快乐心态,这就是他们手中的技能和工具。 有效地处理批评意见 在批评发生的时候——无论是你的游戏完成之后的批评,还是遭遇了反对的声音,要先让自己同被讨论的要点相隔离。当你们对你的工作给予反馈时,无论是针对你的编程、美术 、音频还是其他的,这些都是针对你所创造作品的反馈,而不是针对你本人的批评。 反馈的出发点几乎都是为了让游戏更好更棒,在问题暴露并影响到他人之前,或者在游戏会遭遇重大返工之前指出并修复问题。有时候反馈来得太迟了,延误了项目修复,与其否 定反馈倒不如将其铭记在心并在之后多加用心(毕竟这不是你开发的最后一款游戏或理念,不是吗?)。 防御性姿态通常只会产生事与愿违的结果,至少是浪费有限的时间和精力。 系统和常规渠道 形式和一对一的日常签到会令人感觉官僚作风,但合理的更稳和调节却可以令其发挥重要功能。应该为人们提供一个发表自己看法的渠道,要让大家与项目相关的人进行半常规的 接触,这样才能建立一种信任感,而不至于在发现问题时感觉是在彼此针锋相对,而非提出一些小意见而已。 在我曾参与的一个游戏开发团队中,我们曾试图在还没有开始执行的早期阶段就缩小可能的前进方向。在一次公开的讨论中,大家提出了一些看似可行的想法。当我们让大家举手 表决,看看这些想法的支持率时,我们发现有一个想法仅有廖廖数名支持者——这些支持者是其中最有发言权的参与者。即便只是引进一点形式,也可能给予那些项目中更寡言少 语,但却拥有同样出色想法和考虑之人更多发言渠道,这样团队才好权衡不同的考虑和优先权。 实践,从错误中汲取教训 抓住更多锻炼沟通能力的机会。在所有角色中,在人群中,在正式与非正式场合,在与数人外出途中,与多人外出过程中均是可以利用的机会。 现在,我并不喝酒,也不去酒吧或俱乐部。我几乎从不参加派对。这周末我也没有去看超级杯的打算。我并不是说你应该强迫自己去做那些本不愿意做的事情。我只是想说你应该 去找那些能够让自己放松自如地练习沟通能力的场合。 无论你是单兵作战还是与团队共事,都要好好利用与团队打交道的挑战。去参加会议,参与一些俱乐部活动。如果你所在的团队需要一些消息或花边新闻,要自愿提供这些信息。 沟通是一种游戏开发技能。与任何其他游戏开发技能一样,你通过持之以恒的练习终会获得巨大收获。 相关拓展阅读:篇目1,篇目2(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao) Communication is a Game Development Skill (Part 1 of 2) Today’s subject is an incredibly important one that gets a lot less attention than it should. Most videogame development guides and tutorials fail to acknowledge that communication is a game development skill. Knowing how to speak and write effectively is right up there alongside knowing how to program, use Photoshop, follow design process, build levels, compose music, or prepare sounds. As with any of those skills there are techniques to learn, concepts to master, and practice to be done before someone’s prepared to bring communication as a valuable skill to a team.Game Developers Especially Surely, everyone in the world needs to communicate, and could benefit from doing it better. Why pick out game developers in particular? “…sometimes when people are fighting against your point, they’re not really disagreeing with what you said. They’re disagreeing with how you said it!” I don’t meant to claim that only game developers have communications issues. But after spending much of the past ten years around hundreds of computer science students, indie developers, and professional software engineers, I can say that there are particular patterns to the types of communication issues most common among the game developers that I’ve met. This is also an issue of particular interest to us because it’s not just a matter of making the day go smoother; our ability to communicate well has a real impact on the level of work that we’re able to accomplish, collaboratively and even independently. Game developers often get excited about our work, for good reason, but whether a handful of desirable features don’t make it in because of technical limitations or because of communication limitations, either way the game suffers for it the same. Whose Job is It? If programmers program, designers design, artists make art, and audio specialists make audio, is there a communication role in the same way? There absolutely is. There are several, even. The Producer. Even though on small hobby or student teams this is often wrapped into one of the other roles, the producer focuses on communication between team members, and between team members and the outside world. Sometimes this work gets misunderstood as just scheduling, but for that schedule to get planned and adjusted sensibly requires a great deal of conversations and e-mails, followed by ongoing communications to keep everyone on the same page and on track. The Designer(s). One way to think about the designer’s role in game development is to communicate with the player through the game. Indicating what’s the goal, what will cause harm or benefit, where the player should or shouldn’t try to go next, expressing the right amount of internal state information – these are matters of a game’s design more so than its programming. Depending on a game team’s skill makeup, in some cases the designer’s only direct work with the game is in level layouts or value tuning, making it even more critical that within the team a designer can communicate well with programmers, artists, and others on the team when and where the work intersects. On a small team when the person mostly responsible for the design is also filling one or more other roles (often the programming) communication then becomes integral to keeping others involved in how the game takes shape. The Leads. On a team large enough to have leads, which is common for a professional team, the Lead Programmer, Lead Designer, or Lead Artist also have to bring top notch communication skills to the table. Those people aren’t necessary the lead on account of being the best programmer, designer, or artist – though of course they do need to be skilled – they’re in that position because they can also lead others effectively, which involves a ton of communication in all directions: to the people they lead, from the people they lead, even mediating communications between people they lead or the people they lead and others. Some of the most talented programmers, designers, artists and composers that I’ve met have been quiet people. This isn’t an arbitrary personality difference though. In practice it limits their work – when they don’t speak up with their input it can cost their game, team, or company. The Writer. Not every game genre involves a writer, but for those that do, communication becomes even more important. Similar to the designer that isn’t also helping as a programmer, a team’s writer typically isn’t directly creating much of the content or functionality, aside perhaps from actual dialog or other in-game and interstitial text. It’s not enough to write some things down and call it a day, the writer and content creators need to be in frequent communication to ensure that satisfactory compromises can be found between implementation realities and the world as ideally envisioned. Non-Development Roles. And all that’s only thinking about the internal communications on a team during development. Learning how to communicate better with testers, players, or if you’ve got a commercial project your customers and potential new hires (even ignoring investors and finance professionals), is a whole other world of challenges that at a large enough scale get dealt with by separate HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) specialists, marketing experts, PR

(public relations) people and HR (Human Resources) employees. If you’re a hobby, student, solo, or indie developer, you’ve got to wear all of these hats, too! There are two main varieties of communication issues that we tend to encounter. Although they may seem like polar opposites, in reality they’re a lot closer than they appear. In certain circumstances one can even evolve from the other. Challenge 1: Shyness The first of these issues is that some of us can be a little too shy. Some of the most talented programmers, designers, artists and composers that I’ve met have been quiet people. This isn’t an arbitrary personality difference though. In practice it limits their work – when they don’t speak up with their input it can cost their game, team, or company. It’s unfortunately very easy to rationalize shyness. After all, maybe the reason a talented, quiet person was able to develop their talent is because they’ ve made an effort to stay out of what they perceive as bickering. Unfortunately this line of thinking is unproductive in helping them and the team benefit more from what they know. Conversation between team members serves a real function in the game’s development, and if it’s going to affect what gets made and how it can’t be dismissed as just banter. Sometimes work needs to get done in 3D Studio Max, and sometime it needs to get done around a table. Another factor I’ve found underlying shyness is that a person’s awareness of what’s great in their field can leave their self-confidence with a ding, since they can always see how much improvement their work still needs just to meet their own high expectations. Ira Glass has a great bit on this: It doesn’t matter though where an individual stands in the whole world of people within their discipline, all that matters is that developers on the project know different things than one another. That’s inevitably always the case since everyone’s strengths, interests, and backgrounds are different. Challenge 2: Abrasiveness Sometimes shyness seems to evolve as an overcompensation for unsuccessful past interactions. Someone tried to speak up, to share their idea or input, just to add to someone else’s point and yet it somehow wound up in hurt feelings and no difference in results. Entering into the discussion got people riled up, one too many times, so after one last time throwing hands into the air out of frustration, a developer decides to just stop trying. Maybe they feel that their input wasn’t properly received, or even if it was it simply wasn’t worth the trouble involved. As one of my mentors in my undergraduate years pointed out to me: “Chris, sometimes when people are fighting against your point, they’re not really disagreeing with what you said. They’re disagreeing with how you said it! If you made the same point differently they might get behind it.” He was absolutely right. Once I heard that idea, in addition to catching myself doing it, I began to notice it everywhere from others as well. It causes tension in meetings, collaborative classroom projects, even just everyday conversations between people. Well-meaning folks with no intention of being combative, indeed in total overall agreement about both goals and general means, often wind up in counterproductive, circular scuffles arising from an escalation of unintended hostility. There are causes and patterns of behavior that lead to this problem. After 10 years of working on it, I’ve gotten better about this, but it still happens on occasion, and it’s still something that I have to actively keep ahead of. It’s understandable how someone could run through this pattern only so many times before feeling like their engaging with the group is the cause of the trouble. This is in turn followed by backing off, toning own their level of personal investment in the dialog, and (often bitterly) following orders from the action items that remain after others get done with the discussion. …if you communicate masterfully enough – persuasively, clearly, fairly and reasonably – then the scale and types of projects that it’s possible for you to work on expands tremendously… Last month, in part one, I identified a couple of common points of trouble that arise for videogame developers. Communication matters! If communication skills are in bad enough shape, no matter what other technical or artistic skills have developed it’ll be hard to get others to collaborate, and hard to get players and reviewers to hear about the work. On the other end of the spectrum, if you communicate masterfully enough – persuasively, clearly, fairly and

reasonably – then the scale and types of projects that it’s possible for you to work on expands tremendously, because being a good communicator is essential to winding up as a meaningful part of (or even starting and leading) any team of other developers who are bringing their own respective skills, experience, and inspiration into the picture. Listening and Taking to Heart You’ve heard this all your life. You’ll no doubt hear it again. Hopefully every time communication comes up this gets mentioned too, first or prominently. Listening well, meaning not just hearing what they have to say or giving them an outlet but trying to work with them to get at underlying meaning or concerns and adapting accordingly, is way harder than it sounds, or at least more unnatural than we’d like to think. You can benefit from practicing better listening. I can say that without knowing anything about you, because everyone – presidents and interns, parents and kids, students and teachers – can

always listen better. There’s a tendency, even though we rationally know it’s out of touch with reality, to think of oneself as the protagonist, and others like NPCs. Part of listening is consciously working to get past that. The goal isn’t to get others to adopt your ideas, but rather it’s to figure out a way forward that gains from the multiple backgrounds and perspectives available, in a positive way that people can feel good about being involved with. Don’t Care Who Wins, Everyone Wins There’s no winner in a conversation. This one also probably sounds obvious, but it’s an important one that enough people run into that it isn’t pointed out nearly enough. Development discussion doesn’t need to be a debate. Even to the extent that creative tension will inevitably present certain situations in which incompatible ideas are vying for limited development attention on a schedule, debate isn’t the right way to approach the matter. In one model for how a dialog exchange proceeds, two people with different ideas enter, and at the end of the exchange, one person won, one person lost. I don’t think (hope?) that anyone consciously thinks about dialog this way, but rather it may emerge as a default from the kinds of exchanges we hear on television from political talking heads, movie portrayals of exchanges to establish relative status between characters, or even just our instinctive fight or flight sense of turf. Rather than thinking in terms of who the spectators (note: though avoid spectators when possible, as it can often pollute an otherwise civil exchange with defensive, ego-protecting posturing) or an impartial judge might declare a winner, consider which positions the two people involved would likely take in separate future arguments. If all of your prior references have led you to believe strongly about a particular direction, you only do that rhetorical position (and the team/project!) a disservice by creating opponents of it. Whenever we come across as unlikeable, especially in matters like design, art, or business where a number of directions may be equally viable, then it doesn ’t matter what theoretical support an option has if people associate it with a negative, hostile feeling or person. It doesn’t matter what theoretical support an option has if people associate it with a negative, hostile feeling. Be friendly about it. Worry first about understanding the merits and considerations of their point, then about your own perspective being understood for consideration. Notice that neither of those is about “convincing” them, or showing them the “right” way, it’s about trying to understand one another because without that the rest of discussion just amounts to barking and battling over imagined differences. You Might Just be Wrong Speaking of understanding one another: don’t ever be afraid to back down from a point after figuring out what’s going on, and realizing that there’s another approach that’ll work just as well or better. There’s a misplaced macho sense of identity attached to sticking to our guns over standing up for our ideas – especially when the ideas aren’t necessarily thoroughly developed and aren’t exactly noble or golden anyhow. A smart person is open to changing their mind when new information or considerations come to light. You’re not playing on Red team competing against Blue team. You’re all on the same team, trying to get the ball to go the same direction, and maybe your teammate has a good point about which direction the actual goal is in. You’re all on the same team… The other side of this is to give the other person a way out. Presenting new information or concerns may make it easier for them to change their mind, even if that particular information or concern isn’t actually why they change their mind, simply because it can feel more appropriate to respond to new information then to appear to have been uncertain in the first place. Acknowledging the advantages in the position they’re holding doesn’t make your position seem weaker by comparison, it makes them feel listened to, acknowledged, and like there’s a better chance you’re considering not just your own initial thoughts but theirs too. When a point gets settled, whichever way things go, let the difference go instead of forming an impression of who’s with or against you. (Such feelings have a way of being self-fulfilling. In practice, reasonable people are for or against particular points that come up, not for or against people.) When an idea inevitably gets compromised or thrown out, being a skilled communicator means not getting bitter or caught up in that. Don’t take it personally. It’s in the best interests of the team, and therefore the team’s members (yourself included), that not every idea raised makes it into implementation or remains in the final game. Benefit of the Doubt, Assume the Best A straw man argument is when we disagree with or attempt to disprove a simplified opposition position. In informal, heated arguments over differences in politics or religious/cultural beliefs, these are frequently found in the form of disagreeing with the most extreme, irrational, or obviously troubled members of the group, rather than dealing with the more moderate, rational, and competent justifications of their most thoughtful adherents. This leads to deadlock, since both sides feel as though they’re advancing an argument against the other, yet neither side feels as though their own points have been addressed. Assume that the other person is coming from a rational, informed, well-intentioned place with their position. When the goal is to make a more successful collaboration, rather than to just make ourselves temporarily feel good, the right thing to do is often the opposite of setting up a straw man argument. Assume that the other person is coming from a rational, informed, well-intentioned place with their position, and if that’s not what you’re seeing from what has been communicated so far, then seek to further understand. Alternatively, even help them further develop their idea by looking for additional merit to identify in it beyond what they might have riginally had in mind – maybe from where you’re coming from it has possible benefits that they didn’t

realize mattered to you. If the idea you may be holding is different than what someone else is proposing, welcome your idea really being put to the test by measuring it against as well put-together an alternative as the two of you can conceive. If it gets replaced by a better proposal that you arrived at through real discussion and consideration, or working together to identify a path that seems more likely to pan out well for both of you, all the better. Your Frustration is With Yourself This is one of those little life lessons that I learned from my wrestling coach which has stayed with me well after I finished participating in athletic competitions. Most of the time when people are upset or frustrated or disappointed, they’re upset or frustrated or disappointed mostly with themselves, and directing that at somebody else through blame isn’t ever going to diffuse it. Even if this isn’t 100% completely and totally true in every situation – sure, sometimes people can be very inconsiderate, selfish, or irresponsible and there may be good reason to be upset with them – I find that it’s an incredibly useful way to frame thinking about our emotional state because it takes it from being something the outside world has control over and changes to focus to what we can do about it. Disappointed with someone violating our trust? Our disappointment may be with our failing to recognize we should not have trusted them. Upset with someone for doing something wrong? We may be upset with ourselves for not making the directions or expectations more clear. Frustrated with someone that doesn’t understand something that you find obvious? Your frustration well may lie in your feeling of present inability to coherently and productively articulate to

that person exactly what it is you think they’re not understanding. If your point isn’t well understood or received but you believe it has value that isn’t being rightly considered, rather than assuming the other person is incapable of understanding it, put the onus on yourself to make a clearer case for it. Maybe they don’t follow your reference, or could better get what you ’re trying to say if you captured it in a simple visual like a diagram or flow chart. Maybe they understand what you’re saying but don’t see why you think it needs to be said, or they get what you mean but don’t see the connection you have in mind for what changes you think it should lead to. If your point isn’t well understood or received but you believe it has value that isn’t being rightly considered, rather than assuming the other person is incapable of understanding it, put the onus on yourself to make a clearer case for it. Clarify. Edit it down to summary highlights (people often have trouble absorbing details of an argument until they first already understand the high level). Explain it another way to triangulate. Provide a demonstration case or example. If there’s a point you already made which you think was important to understanding it but that point didn’t seem to stick, find a way to revisit it in a new way that leads with it instead of burying it among other phrases that were perhaps too disorganized at the time to properly set up or support it. Mistaking Tentative for Definitive Decisions can change. When they’re in rough draft or first-pass, they’re likely to – that’s why we do them in rough form first! It’s easier to fix and change things when they’re just a plan, an idea, or a prototype, and the more they get built out into detail or stick around such that later decisions get made based on them, then the more cemented those decisions tend to become. There are two types of miscommunication that can come from this sort of misunderstanding: mistaking your own tentative ideas for being definitive, or mistaking someone else’s tentative ideas for being definitive. During development, and as more people get involved, projects can change and evolve a bit to reflect what’s working or what isn’t, or to take better advantage of the strengths and interests of team members. If there was an idea you pushed for earlier in a project and people seemed onboard with it then, it’s possible that discoveries during development or compromises being made for time and resource constraints have caused it to appear in a modified or reduced form. It might even be cut entirely, if not explicitly then maybe just lost in the shuffle. Before raising a case for it, it’s worth rethinking how the project may have changed since the time the idea was initially formed, to determine whether it would need to be updated to still make sense for the direction the team and game has gone in. Sometimes the value of ideas during development is to give us focus and direction, and whether the idea survives in its originally intended form is secondary to whether the team and players are happy with the software that results. It may turn out to be worth revisiting and bringing back up, possibly in a slightly updated form, as maybe last time was at a phase in development when it wasn’t as applicable as it might be now. Or it may be worth letting go as having been

useful at the time, but perhaps not as useful now, a stepping stone to other ideas and realizations the team has made in the time that has passed. People get optimistic, people make planning mistakes, and people cannot predict the future – but it’s important to not confuse those perfectly human imperfections with knowingly lying or failing to keep a promise. The other side to this is to make the same mistake in thinking about someone else’s ideas: thinking they are definitive when they are necessarily tentative. This happens perhaps because of how far off the idea relates to the future, and how much will be discovered or answered between now and then that is unknown at the time of the initial conception and discussion. If a project recruits people with the intention of supporting a dozen types of cars, but during development reality sinks in and only three different vehicles make sense in favor of putting that energy into other development necessity, those things happen. People get optimistic, people make planning mistakes, and people cannot predict the future – but it’s important to not confuse those perfectly human imperfections with knowingly lying or failing to keep a promise. If early in a project someone is trying to spell out a vision for what the project may look like later, don’t take that too literally or think of it as a contract, look at it as a direction they see things headed in. Implementation realities

have a way of requiring compromise along the way. Soften That Certainty Away A common source of fighting on teams is from a misplaced sense of certainty in an observation or statement which reflects value priorities that someone else on the team doesn’t necessarily share, or especially when the confidently made statement steamrolls value priorities of someone else on team. Acknowledge with some humility that you only have visibility on part of all that’s going on, and that the best you can offer is a clarification of how things look for where you’re coming from or the angle you have on things. Leave wiggle room for disagreement. Little opening phrases like “As best as I can tell…” or “It looks to me like…” or “I of course can’t speak for everyone, but at least based on the games that I’ve played in this genre…” may just seem like filler, but in practice they can be the difference between tying the team in a knot or opening up valuable discussion about different

viewpoints. Consultant’s Frustration School surrounds people with other people that think and work in similar patterns, with similar values, often of the same generation. Outside the classroom, whether collaborating on a hobby game project, joining a company, or doing basically anything else in the world besides taking Your Field 101, that isn’t typically how things work. Often if your skills are in visual art, you have to work with people that don’t know as much about visual art as you. If your skills are in design, you’ll have to work with a lot of non-designers. If you have technical talents, you will be dealing with a lot of non-technical people. That is why you are there. Because you know things they don’t know. You can spot concerns that they can’t spot. You understand what’s necessary to do things that they don’t know how to do. If someone else on the team or company completely understood everything that you understand and in the same way, they wouldn’t really need you to be involved. Your objective in this position is to help them understand, not to think poorly of them for knowing different

things than you do. Help them see what you see. Teach a little bit. That is why you are there. Because you know things they don’t know… Your objective in this position is to help them understand, not to think poorly of them for knowing different things than you do. Help them see what you see. I refer to this as the consultant’s frustration because that’s a case that draws particular emphasis to it: a company with no understanding of sales calls in a sales (or design, or IT, or whatever) consultant, because they have no understanding of that and that’s why they made the call. A naive, inexperienced, unprepared consultant’s reaction to these situations is one of horror and frustration – how on Earth are these people so unaware of the basic things that they need to know? The consultant is there to spot that gap and help them bridge it, not to look down on them for it. Meanwhile they’re doing plenty of things right the specialist likely doesn’t see or fully understand, because that’s not the discipline or problem type that they’re trained and experienced in being able to spot, assess, or repair. When you see something that concerns you, share that with the team. That is part of how you add value. You may see things that others on the team do not. Values Are Different Per Role The other side to the above-mentioned point is appreciating that other factors and issues less visible to your own vantage point may have to be balanced against this point, or in some cases may even override it. Frustration can arise from an exaggerated form of the consultant’s frustration: a programmer may instinctively think of other roles on the team as second- rate programmers, or the designer may perceive everyone else on the team as second-rate designers, etc. This is not a productive way to think, because it’s not just that they are less-well suited to doing your position, but you’re also less-well suited to doing theirs. A position goes beyond what skills someone

brings to move a project forward, it also brings with them an identity and responsibility on the team to uphold certain aspects of the project, a trained eye to keep watch for certain kinds of issues. The programmer may not be worried about the color scheme, the artist may not be worried about how the code is organized, the designer may not care about either as long as the gameplay works. …a programmer may instinctively think of other roles on the team as second-rate programmers… That’s one of the benefits of having multiple people filling specialized roles, even if it’s people that are individually capable of wearing multiple hats or doing solo projects if they had to. In the intersection of these concerns, compromises inevitably have to get made. The artist may be annoyed by a certain anomaly in how the graphics render, but the engineer may have a solid case for why that’s the best the team’s going to get out for the given style of the technology they have available. The musician or sound designer may feel that certain advanced scoring and dynamic adjustment methods could benefit the game’s sounds cape, but the gameplay and/or level designer may have complications they’re close to about user experience, stage length, or input scheme that place some tricky limits on the applicability of those approaches. One of the reasons why producers (on very small student/hobby/indie teams this is often also either the lead programmer or lead designer) get a bad rap sometimes, as the “manager” that just doesn’t get it, is because their particular accountability is to ensure that the game makes forward progress until it’s done and released in a timely manner. So the compromise justification that they often have to counter with is, “…but we have to keep this game on

schedule” which is a short-term version of “…but this game has to get done.” If someone isn’t fighting that fight for the project, it doesn’t get done. Be glad that other people on a team, when you have the privilege of working with a good and well-balanced team, are looking out for where you have blind spots. Push yourself to be a better communicator so that you can help do the same for them. Too Much Emphasis on Role After that whole section on role, I feel the need to clarify that especially for small team development (i.e. I can total understand military-like hierarchy and clarity for 200+ person companies) role shouldn’t pigeonhole someone’s ability to be involved in discussions and considerations. While it’s true that the person drawing the visual art is likely to have final say on how the art needs to be done (not only as a matter of aesthetic preference, but as a side effect of working within their own capabilities, strengths, and limitations), that does not mean that others from the team shouldn ’t be able to offer some feedback or input in terms of what style they feel better about working with, what best plays to their own strengths and mmer’s going to be able to support it in real-time), and what they like just as fellow fans of games and media. Does one team member know more about animation than others on the project? Then for goodness sake, of course that person needs to be involved in discussions affecting the implementation or scheduling of animation. But even if you’re not an animator, that you’ve accumulated a different set of media examples to draw upon, and have an idea for how that work may intersect with technical, design, or other complications, there’s still often value in being a part of that discussion (though of course still leaving much of the decision with whoever it affects most, and whoever has the most related experience). It’s unhelpful to hide behind your role… It’s unhelpful to hide behind your role, thinking either “Well, I’m not the artist so that isn’t my problem” or “Well, I’m the designer, so this isn’ t your problem to worry about.” The quality of the game affects everyone who got involved with making it. You make a point of surrounding yourself with capable people that are coming from different backgrounds and have different points of view to offer. Find ways to make the most of that. A related distinction to these notes about role is the concept of servant-leadership. Rather than a producer, director, or lead designer feeling like the boss of other people who are supposed to do what they say, it can be healthy and constructive for them to approach the development as another collaborator on the team, just with particular responsibilities to look out for and different types of experience to draw from. They’re having to balance their own ideas

with facilitating those of others to grow a shared vision, they’re trying to keep the team happy and on track, that’s their version of the compiler or Photoshop. Handling Critique Productively When critique comes up – whether of your game after it’s done or of a small subpoint in a disagreement – separate yourself personally from the point discussed. When people give feedback on work you’re doing, whether it’s on your programming, art, audio, or otherwise, the feedback is about the work you’ re doing, it’s not feedback about you (even if, and let’s be fair here, we could all honestly benefit from a little more feedback about ourselves as a work-in-progress, too!). Feedback is almost always in the interest of making the work better, to point out perceived issues within a smaller setting before it’s too late to fix the work in time for affecting more people, or before getting too far into the project to easily backtrack on it. Sometimes the feedback comes too late to fix them in this case, in which case rather than disagree with it accept that’s the case and keep it in mind to improve future efforts (this isn’t the last game or idea you’re ever going to work on, right?). Defensiveness, of the sort mentioned in the recent playtesting entry, is often counterproductive, or at lease a waste of limited time and energy. Systems and Regular Channels Forms and routine one-on-one check-in meetings can feel like a bureaucratic chore, but in proper balance and moderation they can serve an important function. People need to have an outlet to have their concerns and thoughts heard. People need to be in semi-regular contact with the people who they might need to raise their concerns with, before there is a concern to be raised, so that there’s some history of trust and prior interaction to build upon in those cases and it doesn’t seem like a weirdly hostile exception just to bring up something small. In one of the game development groups I’ve been involved with recently we were trying to narrow down possible directions for going forward from an early stage when little had been set into action yet. From just an open discussion, three of the dozen or so ideas on the whiteboard got boxed as seeming to be in the lead. When we paused to get a show of hands to see how many people were interested in each of the ideas on the board, we discovered that one of the boxed

items had only a few supporters – those few just happened to be some of the more vocal people in the room. Even introducing just a tiny bit of structure can be important in giving more of an outlet to the less outspoken people involved with a project, who have ideas and considerations that are likely just as good and, as mentioned earlier, probably weighing different sets of concerns and priorities. Practice, Make Mistakes to Learn From Seek out opportunities to get more practice communicating. In all roles, and at all scales. As part of a crowd. In front of a crowd. In formal and informal settings. Out with a few people. Out with a lot of people. Now, for personal context: I don’t drink. I don’t go to bars or clubs. I’ve admittedly never been one for parties. This weekend I have no plans to watch the Super Bowl. I’m not saying you should force yourself to do things that you don’t want to do. What I am saying is to look for (or create) situations where you can comfortably exercise your ommunication abilities. Whatever form that may take for you. Seek out opportunities to get more practice communicating. Given a choice to work alone or work with a group, welcome the opportunity to deal with the challenges of working with a group. Attend a meetup. Find some clubs to participate in. When a team you’re on needs to present an update, volunteer to be the one presenting that update. Communication is a game development skill. As with any other game development skill, you’ll find the biggest gains in ability through continued and consistent practice.

|